Why do so many high-performing professionals keep working at a punishing pace, even when it damages their health, relationships, and personal well-being? And why do organizational attempts to curb these extreme work hours—no-email-after-hours policies, mental health initiatives, or wellness seminars—so often fail?

Our forthcoming research reveals a powerful and often overlooked mechanism driving this behavior: the “entrainment cycle.” Drawing on more than 150 interviews in global law and accounting firms, we found that professionals become emotionally and physically synchronized with their organization’s relentless tempo, creating a powerful feedback loop that locks them into a culture of overwork.

While high-tempo work cultures may appear efficient and profitable in the short term, the long-term costs for organizations are substantial—and often underestimated. These can include burnout-driven attrition (particularly among high performers); limited space and time for creativity; lower productivity and higher rates of errors; and an unusually fragile work culture—all reliant on the adrenaline of constant motion. In moments of slowdown or crisis, such as economic downturns or leadership transitions, this pace-dependent loyalty can evaporate, leaving disengaged teams, quiet quitting, or sudden departures in its wake, as seen during the Covid-19 pandemic.

So what can organizations do to future-proof themselves against the heavy costs associated with high tempos? We draw upon our study to offer insight into what causes entrainment cycles, how to break them, and what companies should do instead to maintain profitability while supporting employee health, well-being, and retention.

The Costs of Entrainment

In many elite professional service firms, long hours are more than just a habit—they’re a way of life. Employees routinely work evenings, weekends, and holidays, not simply because they’re told to, or they’re particularly driven or “type-A,” but because they’ve come to feel that pace is normal—even necessary.

Our study found that these high-tempo organizations share similar characteristics, including:

- Formal timekeeping systems, like utilization rates and timesheets, which push employees to track every half hour, fostering a constant sense of urgency.

- Career advancement systems (e.g., up-or-out promotion models and performance evaluation systems) that challenge professionals to continually meet escalating performance targets year after year.

- Cultural expectations—reinforced by managers and peers—that frame overwork as virtuous and normal, making boundary-setting feel like disengagement.

Together, these performance management and control systems don’t just influence behavior; they shape how people feel when they’re working—and when they’re not.

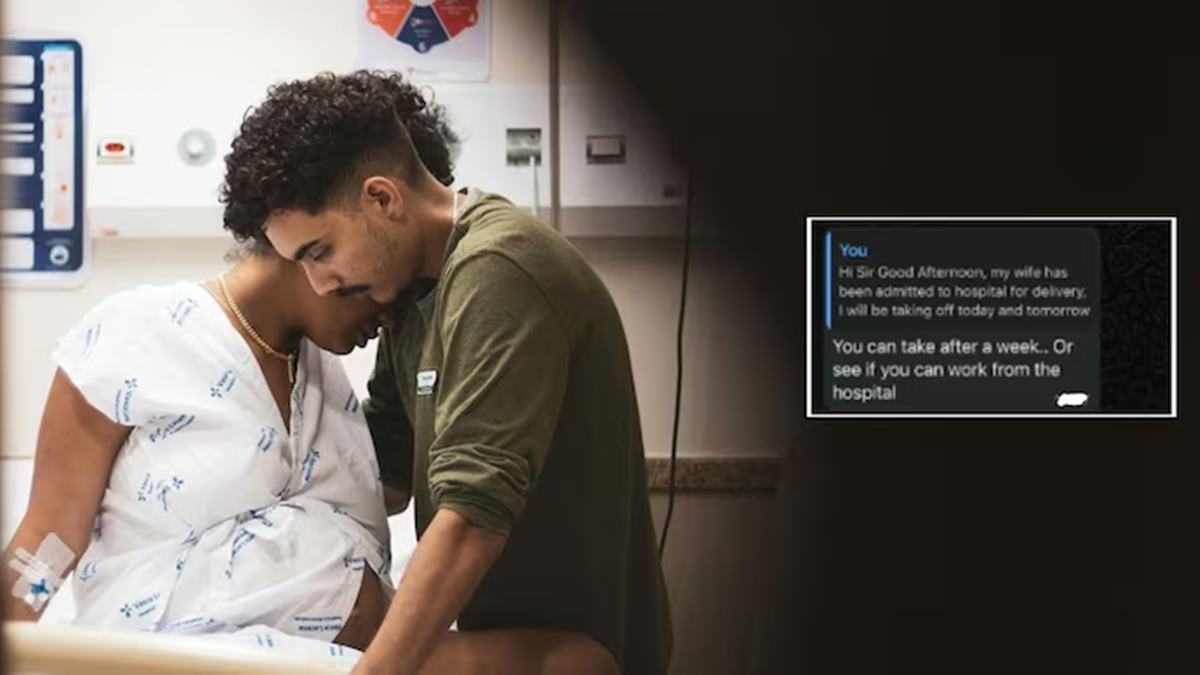

Our research found that when employees fall out of sync with their companies (for example, during holidays or quiet periods), they often experience negative emotions such as anxiety, boredom, guilt, and even physical withdrawal symptoms. One woman partner in an audit firm described falling ill at the start of holidays—a typical example of the let-down effect, a phenomenon where the body, after prolonged stress, becomes vulnerable to illness as stress hormone levels drop.

The interplay between the positive reinforcement professionals experience when synchronized with intense work patterns and their adverse reactions when they’re out of sync exerts a strong psychological and embodied grip on individuals. This makes it challenging for them to disengage from the rhythms of work, even when the personal costs become apparent. As a male partner in a law firm notes:

When I’m busy, generally speaking, I am more energized…When I’m not busy then the pressures that come with not being busy because of all the financial metrics and all that sort of thing that we’re judged against…It can be a nightmare because…You get down on yourself and then you’re probably like a bear with a sore head at home as well.

Why People Stay in the Cycle

Employees in the study often described the fast-paced tempo of work not as something they were forced into, but as something they craved—or at least couldn’t function well without. One described the “adrenaline” of deadlines; another admitted they became “bored” without it. Even physical health was affected: One participant’s Apple Watch showed a sharp rise in resting heart rate during busy seasons, while others described taking antidepressants to get through particularly demanding periods, and others mentioned excessive drinking to try to decompress.

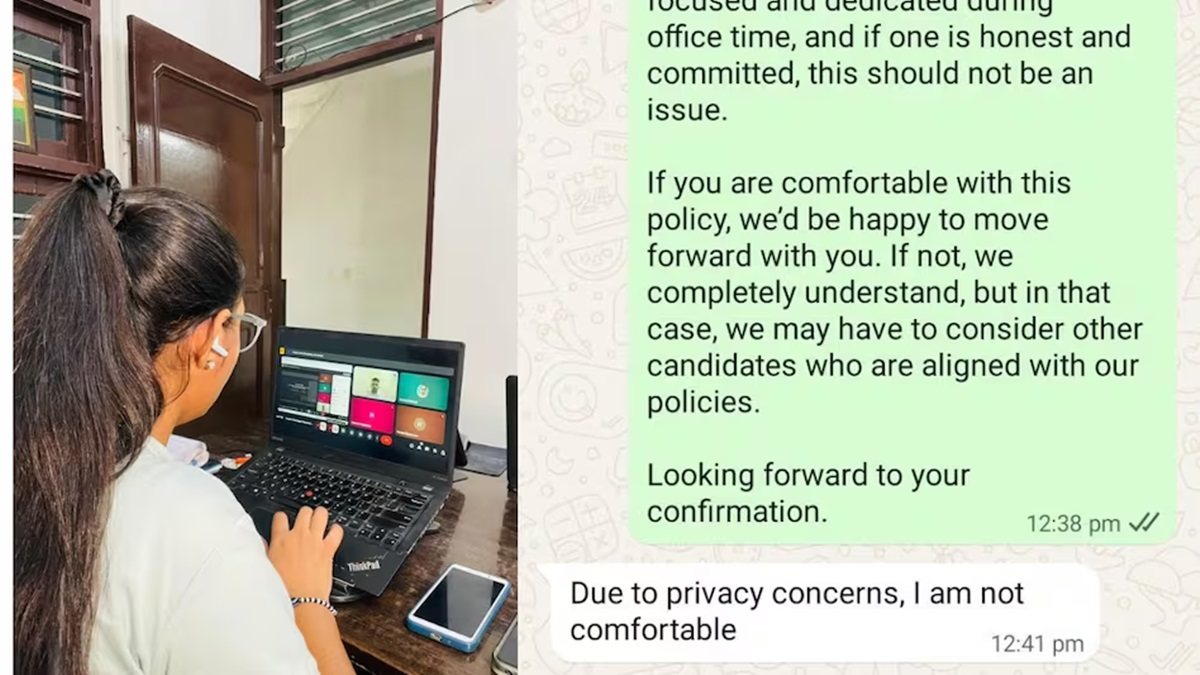

Critically, even when professionals tried to disconnect—during leave, illness, or family emergencies—the firm’s tempo lingered in their minds. They feared falling behind, missing opportunities, or appearing less committed. As one participant, a partner in a law firm, told us: “When we’re on holiday, I’d like to check that there’s nothing, otherwise I panic that there’s something happening that I don’t know about. And the children do notice that and they don’t like it.” Similarly, in an attempt to minimize the disruption of work on family time, another participant reported hiding in the bathroom to call a client on Christmas day.

One finding of our research was that the more people became synchronized with their organization’s rhythm, the more estranged they became from their own biological rhythm and the rhythm of their family life. For example, many participants reported skipping meals, experiencing sleep disturbances, and connecting with work during holidays with loved ones. This deep internalization of organizational rhythms means that even voluntary overwork is not necessarily a sign of engagement—it can be a sign of organizational entrapment.

Breaking the Cycle: What Leaders Can Do

The entrainment cycle is subtle but powerful. But organizations can design interventions to loosen its grip—if they understand what they’re up against. Here’s where to start:

Address the tempo, not just the hours.

To break entrainment, organizations must change how work is done. That means, for instance, rethinking project pacing, reducing artificial urgency, and redesigning calendars to allow for focus and reflection. It implies a shift from reactive busyness to proactive planning.

One example of a systemic intervention is the introduction of a four-day workweek. If done thoughtfully, this restructure sets a firm boundary that forces teams to prioritize, streamline, and recalibrate their tempo—not just compress the same overload into fewer days. Rather than individuals managing their calendars differently, the entire organization shifts its operating cadence, prioritizing greater work-life balance. In 2021, the United Kingdom–based Atom Bank shifted to a four-day workweek without cutting employee pay. This wasn’t just about fewer hours; it meant redesigning meetings, project cycles, and planning norms. After two years, the company reported that the shift had led to lower absenteeism, improved morale, sustained productivity—and better profitability.

In order to address the constant pressure to be “on,” Basecamp, a software company known for its project management tools, prioritizes asynchronous communication and minimal meetings, encouraging employees to take their time writing emails rather than being bound to responding to real-time chats or hopping on to last-minute calls. This allows team members to respond on their own schedules and work without fear of missing something, fostering deeper focus and meaningful engagement.

Another example of a useful change to break entrainment cycles is German automaker Mercedes-Benz’s “Mail on Holiday” email policy, which ensures its employees are taking full advantage of their time off, without fearing an overflowing inbox when they return. Through this policy, emails received during holidays are auto-deleted, and a note is sent to the sender, conveying that they will need to reach out once the employee has returned to the office. This allows employees to disconnect from the office rhythm without anxiety about missing something. Moreover, quite often, the fear of coming back from the holiday and facing an inbox full of hundreds of messages made many employees in our study check and delete unnecessary emails during holidays. One interviewee reported feeling the need to delete messages even while in the queue to see the historic Sagrada Família in Barcelona. While this policy is optional at Mercedes Benz, it provides a good model for what organizations can do help interrupt harmful synchronization.

Watch for warning signs—and keep making adjustments.

One reason entrainment is so powerful is because it’s invisible. Over-synchronized employees often appear committed and productive, but beneath the surface, they may be struggling to disconnect, experiencing sleep problems, or losing a sense of purpose—compulsion disguised as dedication.

The U.S.–based marketing company Buffer offers a good example of a company that has made both systemic changes to address overwork while continuing to monitor how its employees are feeling. In 2020, it introduced a four-day workweek alongside weekly “energy check” surveys that ask employees about flow, overwhelm, and engagement. The data helps managers adjust workloads and prevent burnout. After the rollout, employees reported feeling more productive, and objective productivity among the engineering staff also increased. However, after some employees noted that they struggled to complete tasks in fewer days during busy seasons, Buffer created a more fluid system, allowing the fifth day to become, if necessary, an overflow day. However, if a fifth day is used, employees are told to compensate by working less other weeks.

Another thing large companies can do to stay attentive to employees’ well-being is to start leveraging the data to proactively detect and address early signs of over-entrainment in different teams or departments. For example, the consulting firm BearingPoint uses an AI-driven mental health platform, Teale, which, through various tools including an AI-powered coach, provides monthly anonymized dashboards (with aggregated data to protect employee privacy). This dashboard enables managers to gain strategic insight into workload distribution, team dynamics, and overall organizational climate reported by employees. It allows managers to spot signs of stress, disengagement, and burnout early, and respond before issues escalate.

. . .

While our research focuses on professional service firms—particularly in law and accounting/consulting—many of the dynamics we observed, such as organizational entrainment and the costs of constant synchronization, are highly relevant to any high-tempo, project-based organization. If leaders want sustainable performance, they must break the link between speed and success—and help their teams find a more human pace. This implies creating a new collective rhythm at a more human-centered tempo, rather than forcing individuals to follow the relentless organizational rhythm.

Additionally, people should feel that they have the cultural permission to pause. It is not enough to change schedules—companies have to change expectations. Taking breaks, disconnecting on non-work days, and ignoring the inbox when on holidays should become organizational norms, not individual exceptions. The emotional sync with work intensity could thus be disrupted, allowing people to develop healthier personal rhythms.

Source – https://hbr.org/2025/07/new-research-on-why-teams-overwork-and-what-leaders-can-do-about-it