As a child, I watched a labour union leader address a gathering. “Eight hours of work, eight hours of rest, eight hours of entertainment or leisure,”his voice echoing through a loudspeaker. In Hindi, it had rhythm: 8 ghanta kaam, 8 ghanta aaram, 8 ghanta manoranjan. It was the foundational principle of organised labour—a demand fought for through strikes and sacrifice, eventually codified into law.

That was decades ago. Somewhere between then and now, that principle evaporated.

Anna Sebastian Perayil was 26 years old. She worked at EY Pune and died in July 2024, her death attributed to work-related stress. Kerala’s response—the Right to Disconnect Bill 2025—is genuine legislative ambition. But it’s also an admission of how completely we’ve abandoned what labour movements once achieved.

The bill includes specific prohibitions, investigative powers, and constitutional grounding in Article 21. District grievance committees chaired by Regional Joint Labour Commissioners will investigate complaints and recommend punitive action. Employers who retaliate face legal consequences.

This deserves respect. But feasibility is another matter entirely.

What the Bill gets right

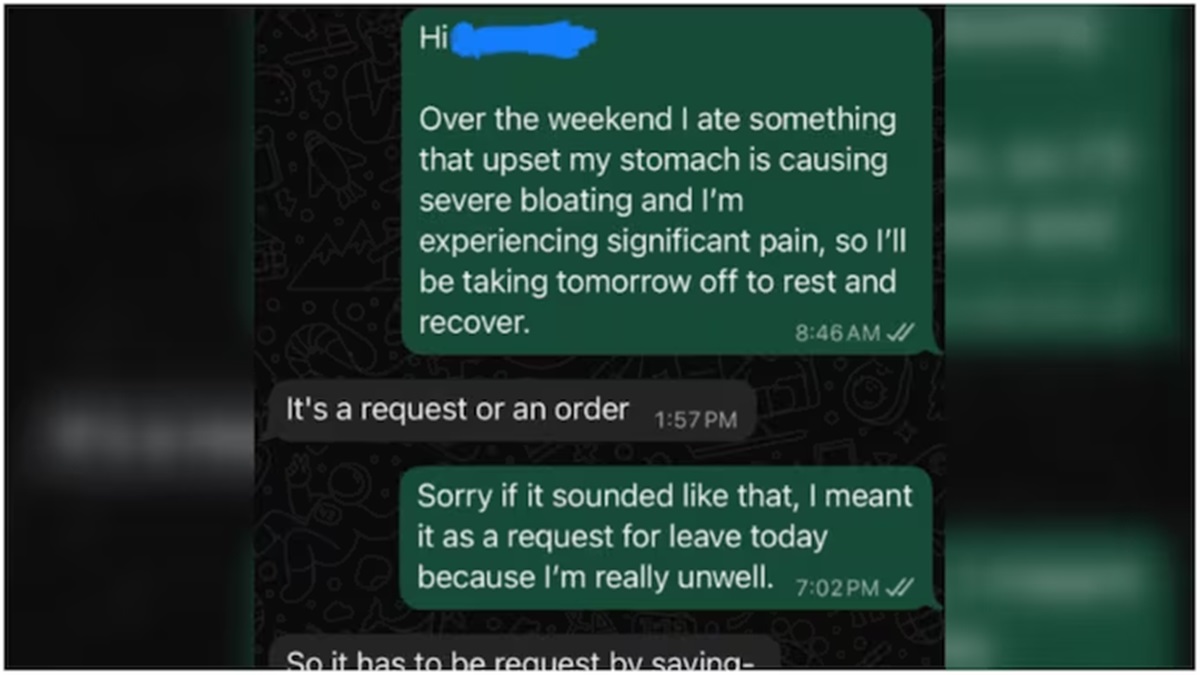

After COVID-19 normalised work-from-home, the boundary between office and home dissolved. Emails arrive at midnight. Slack messages interrupt weekends. Productivity software monitors bathroom breaks. The bill correctly frames this as labour exploitation, not personal stress management.

The constitutional grounding matters. By anchoring the right to disconnect in Article 21—dignity and rest as fundamental to human life—Kerala elevates this beyond employment law into fundamental rights territory. This could inform how other states approach workplace protections.

The inclusion of investigative committees distinguishes this from France’s largely unenforced right to disconnect. Kerala is attempting actual accountability.

The principle we lost

As economies shifted from manufacturing to services, something fundamental shifted too. The 8-8-8 principle—codified in factory acts and labour codes—was premised on physical work. You worked for 8 hours, your body rested for 8 hours, you lived for 8 hours. That division was clear. That boundary was visible.

Then technology erased it.

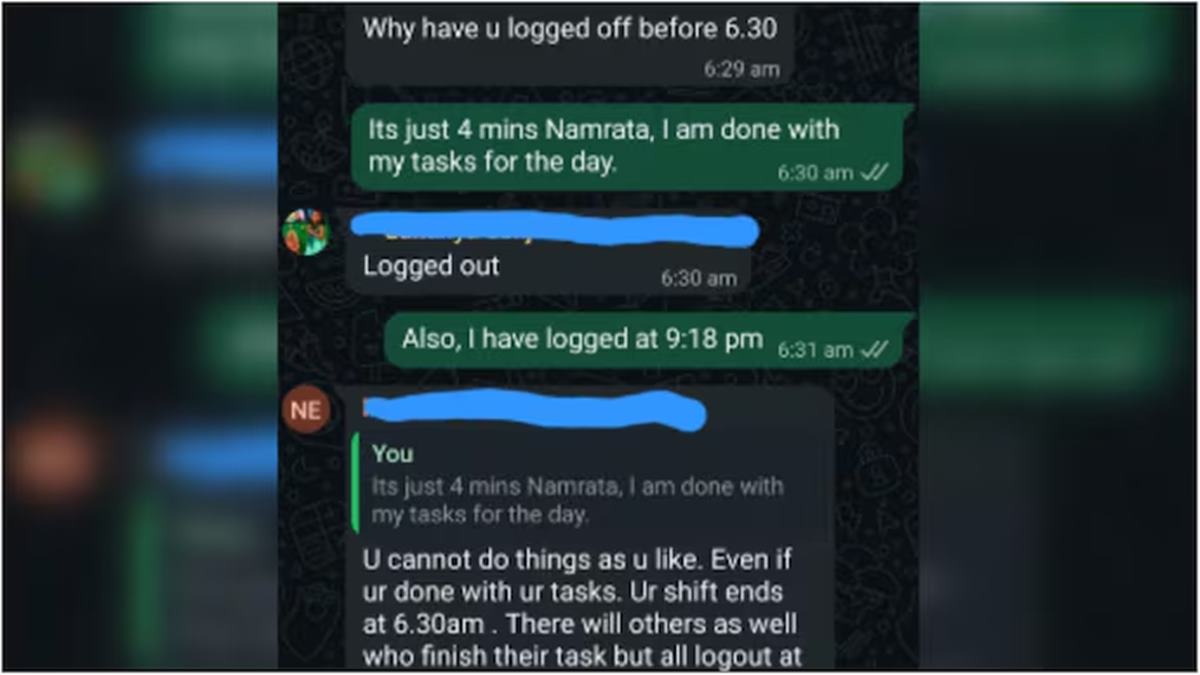

Services economies don’t work like factories. They operate globally. Email doesn’t care about time zones. A coding bug doesn’t wait until morning. Client emergencies are never truly emergencies, but they’re framed as if the world will collapse without immediate response. WhatsApp messages from managers don’t feel like work—they feel like urgency.

Somewhere in this transition, we convinced ourselves that availability had replaced skill as the measure of dedication. We transformed work from something you do into something you are. We created a world where nothing can wait and everything is critical. Where every minor issue gets inflated into a life-changing emergency. Where the quest for endless growth justifies endless availability.

Has technology enabled this, or simply revealed what employers always wanted? The answer matters less than recognising what happened: we abandoned the 8-8-8 principle not because labour movements failed, but because we forgot why they fought for it.

Can law restore what we forgot?

This is where Kerala’s bill becomes more significant than its enforcement provisions suggest. The bill may not prevent a single overworked employee from responding to evening emails. Grievance committees may investigate retaliation and fail to prove it. Employers may find legal workarounds. All of this is likely.

But the bill serves a different function: it reminds us what we lost. It reintroduces the principle that humans require rest, that leisure isn’t laziness, that work shouldn’t consume your entire existence. It places a historical marker saying, “This matters. We should remember this.”

Perhaps that’s the real value. Not enforcement but remembrance. Not punishment but recalibration. A moment to ask: when did we accept that being reachable at all hours was normal? When did we decide that the 8-8-8 principle was naive?

But enforcement and intention diverge dramatically.

The proof problem: The bill prohibits retaliation. Yet modern retaliation is rarely explicit. An employee refusing evening emails isn’t fired outright. She’s simply “not collaborative enough.” Her appraisals suffer. She’s overlooked for promotion. How do district committees prove that a denied promotion equals retaliation for disconnecting? They cannot. The burden falls on the employee to demonstrate causation between her disconnection and career stagnation—essentially impossible to prove.

The precarity trap: The bill assumes workers have security to exercise their rights. Contract workers, freelancers, and junior employees lack this security. A junior developer on a three-person team cannot disconnect when her absence is immediately visible. The bill treats all workers identically despite vast differences in actual power.

The sector exemption collapse: Finance, IT, and consulting will claim critical-sector status requiring 24/7 availability. Within years, most ambitious workers will find themselves in supposedly “critical” sectors where exceptions apply.

The cultural resistance: Workplace norms run deeper than law. Disconnecting signals lack of ambition. Your colleagues working weekends get promoted faster. You can have a legal right to disconnect and still face career consequences, as long as those consequences are framed as performance rather than retaliation.

Will it actually matter?

The real test isn’t the bill’s wording—it’s whether overworked district committees will investigate subtle retaliation, whether companies face meaningful consequences, and whether employees will actually invoke their rights despite career fears.

France enacted its right to disconnect in 2016. Nearly a decade later, enforcement remains inconsistent. Workers rarely file complaints because the process is lengthy and outcomes uncertain. India’s governance infrastructure is weaker than France’s. District committees will be understaffed. By the time a committee rules that retaliation occurred, the employee has likely moved to another job.

The practical impact depends less on legal penalties than on voluntary corporate adoption. Some tech companies already experiment with genuine disconnect policies—not legal compliance but cultural change—driven by talent competition and recognition that burnout is expensive. The bill could accelerate this trend by raising regulatory risk.

The broader significance

Whether Kerala’s bill succeeds or fails, it marks a crucial shift. It recognises that existing labour law—written for factory floors and fixed hours—cannot regulate digital work where employer reach is unlimited. By introducing the right to disconnect, Kerala signals that this gap must be addressed.

Even with limited enforcement, it reframes the conversation. No longer can employers claim that always-on work is simply the cost of ambition. Now it carries legal consequences.

The uncomfortable reality

Anna’s death was real. The burnout crisis is real. Kerala’s legislative response is real and serious.

But laws don’t prevent tragedies. They merely address them after the fact. The bill cannot guarantee that no young professional will work themselves to death again. It can only make employers reconsider the culture that leads to such outcomes. It can only protect workers secure enough to invoke their rights. It can only provide redress for those brave enough to risk their careers on ambiguous grievance processes.

That’s not nothing. But it’s also not the complete solution the tragedy demands.

Real prevention requires what no law can mandate: employers choosing humanity over productivity and a fundamental cultural shift away from viewing exhaustion as a badge of honour.

Kerala’s bill creates the legal framework for that possibility. Whether the state actually builds the infrastructure, trains the committees, and enforces the provisions will determine whether Anna’s legacy becomes genuine protection or another well-intentioned law that sounds progressive but changes little.

That’s the practical challenge Kerala now faces.

Source – https://www.hrkatha.com/special/editorial/the-8-8-8-principle-we-forgot/