About three generations ago, work ended either with a whistle or by punching out a card. The factories were shut down, the machines cooled down and as soon as you stepped out of the gates, you were free to spend your day however you wanted. Home meant home, and work was work. Two separate worlds that didn’t necessarily collide.

Today that divide has all but disappeared.

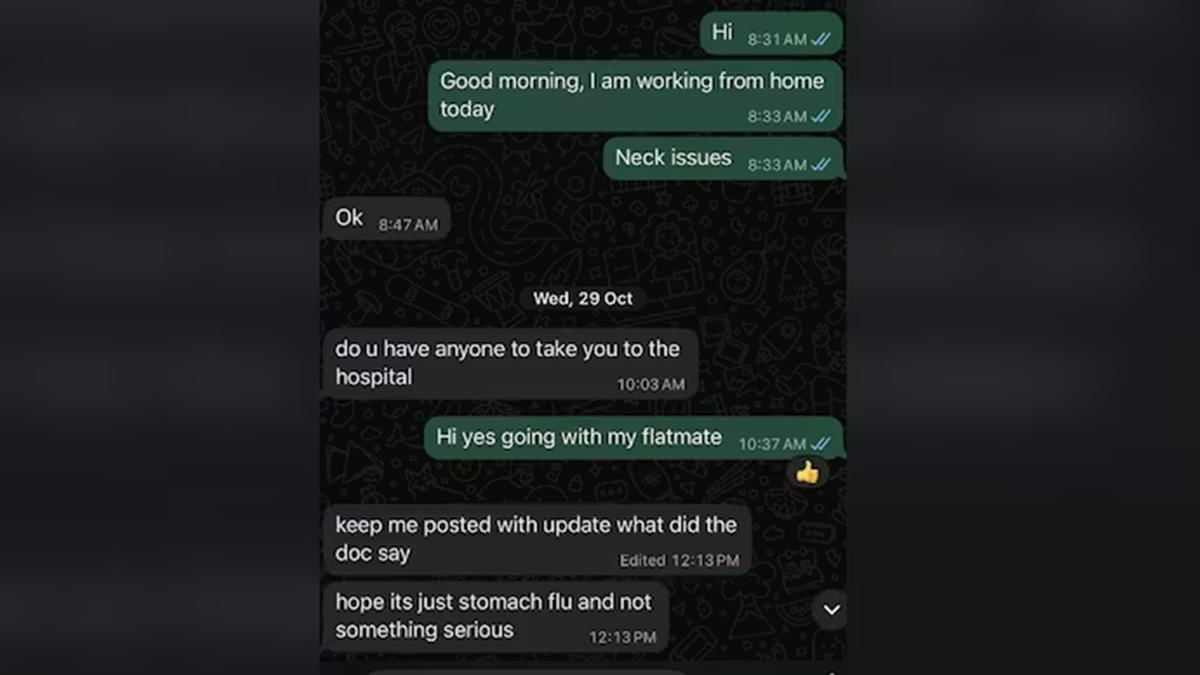

It’s a Friday evening. You’re done for the week. Saturday couldn’t have arrived sooner and just as you’re about to shut down your laptop, that one message pops up: ‘Can we connect?’

For millions of formal workers across India, this has become the norm: Extending work hours well after logging out. For years, this has been the unspoken rule: The phone buzzes, you answer. Doesn’t matter if it’s dinner time, a weekend, a holiday, a vacation — work follows us everywhere.

The internet boom didn’t necessarily help our cause. With affordable data, we switched to an ‘always online’ mode, and with it, the line between work and home disappeared. And it’s not just us saying it. Take a look at any major report on burnout and overworking, and you’ll find Indians are always at the top of the list as the most overworked.

For context, a 2023 report by McKinsey Health Institute suggests that 59% of Indian employees experience burnout. But here’s the thing. This reflects only the people who actually took the survey. But there’s lots of other employees who probably experience burnout. Their concerns don’t necessarily make it to published studies or government reports.

And honestly, this isn’t just an Indian problem. In the past eight years, country after country began adopting their own versions of the Right to Disconnect Act. Back in 2017, France became the first country to pass its own right to disconnect law. Until then, this was never heard of before, making it a landmark change in the world.

One after the other, countries across Europe and beyond started following France by making their own versions of the right to disconnect as technology and the internet blurred the lines between work and life. But somehow, India never made it to this list and workers here continued to work extra hours, after clocking out and well ahead of their logout time.

Companies weren’t going to complain about it or force them to go home because it’s essentially free labour every hour and minute spent extra, working. Even the concept of overtime pay is something that’s only recently making the rounds, but there’s a good chance that most companies still don’t follow it to the dot.

Despite the mounting evidence that India badly needed a labour law for the right to disconnect, we never passed our own version. This is why, back in 2018-19, Member of Parliament (MP) Supriya Sule introduced the first version of the Right to Disconnect Bill. And looking back there was enough mounting evidence that we needed it now more than ever.

The framework of the bill made certain things quite clear. For example, say you don’t answer an email from your employer after you’ve logged out for the day. In a normal circumstance, that’s enough to cause anxiety over what’s gonna happen tomorrow. But going by the bill, you wouldn’t have to worry because it clearly stated that the employee wouldn’t be subject to any disciplinary action by the employer.

One of the main points of the bill was to have an Employees Welfare Authority just to have the right to avoid work-related calls after work or on holiday, without the employees risking their jobs and performance for doing it.

If implemented, the Bill would require companies to limit non-urgent after-hours communication and ensure no employee’s appraisal, bonus or promotion is affected by their decision to disconnect.

These kinds of provisions made it a revolutionary bill… if it passed.

But despite the promises the bill made, it didn’t move further ahead and so nothing changed. Workers continued on with their day — late-night emails, weekend calls and interrupted holidays. With that, we continued to follow that unspoken rule — availability equals commitment. Somewhere along the way, all of us might have wondered or wanted to know — What happened to the bill and why didn’t it pass?

The fact that it didn’t become law despite the clarity and intentionality, had nothing to do with the bill itself. Rather, it had to do with the fact that it was a Private Member bill.

Here’s why. A Private Member’s bill is any bill that is introduced by an MP who’s not a minister. The general trend is that the bills they propose raise very important issues and debates, but they almost never become the law. Such bills rarely become law because they rarely receive government backing, and without that support, they have almost no chance of being passed. In fact, only 14 private member bills have passed as laws since early Independence.

But here’s the thing. Despite low odds of being passed as a law, it doesn’t stop MPs from raising their concerns. Because even if it doesn’t become reality today, it at least plants the seed.

So while the Right to Disconnect Bill didn’t pass back in 2019, it definitely presented an important argument. Between then and today, the world changed. Remote work became real, very quickly. Teams spread across time zones and the digital leash only became more evident. Burnout became a national talking point as situations changed.

Which is also why, for the first time since Supriya Sule introduced the bill, the question came back at a national level — Is India finally ready to legislate the right to disconnect?

The timing couldn’t have been better. Many Indian leaders were calling for longer work hours, new labour codes were on the horizon, and an entire workforce was learning to live with being perpetually online. So when Sule reintroduced the bill in the Lok Sabha this year, it landed in a country where burnout had only grown since the pandemic, giving the proposal much stronger legs to stand on.

To put things in perspective, an average Indian worker puts in about 48 hours of work per week, which is honestly among the highest worldwide. And burnout actually reduces productivity, contrary to what the hustle culture promotes. The best proof of concept is seen in the countries that adopted it.

Surveys across Europe showed that workers reported better work-life balance, improved health and job satisfaction when they were able to unplug after work hours without damaging their careers. Over 70% of workers in companies with a right to disconnect policy were very or somewhat positive.

Now even with the reintroduction of the bill, it doesn’t guarantee that it will become the law. But it sets the stage for the shift. The reintroduction of the Right to Disconnect Bill signals that India is finally ready to ask a long-overdue question — how much of our lives should work be allowed to consume?

Whether the law passes this year or evolves through future drafts, the conversation has begun, and it will only grow louder. Until then, over 50 crore Indian workers will closely watch and hope.

Source – https://finshots.in/archive/why-india-needs-the-right-to-disconnect/