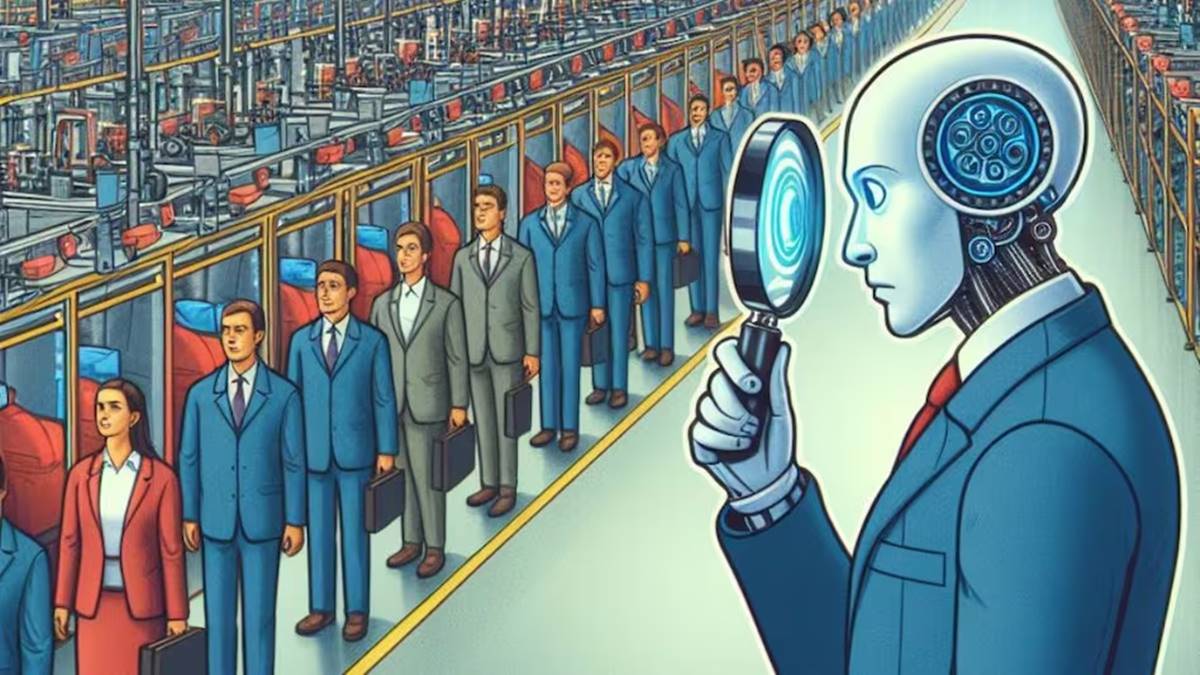

A new study from Anthropic suggests that the relationship between artificial intelligence and employment may be more incremental and complicated than current discourse suggests.

The latest edition of the Anthropic Economic Index, released last week, analyzed roughly two million anonymized Claude conversations from last year, across both free and paid versions of the AI product. The report looked at how people are using AI at work and how those uses are changing jobs in practice.

Notably, rather than job destruction, the headline finding is job fragmentation: According to the study, 49% of U.S. jobs now involve tasks where AI can be used for at least a quarter of the work involved, up from 36% in early 2025. In most cases, AI is taking over pieces of those jobs.

“Combining across reports, 49% of jobs have seen AI usage for at least a quarter of their tasks,” the report states. “But incorporating that task’s share of the job, and Claude’s average success rate, suggests a different set of affected occupations.”

Researchers classified Claude interactions by purpose — work, education, personal use — and then explored how AI was being deployed within work tasks. Some users asked Claude to complete tasks end-to-end, such as translating text and summarizing documents, while others worked with the system iteratively, using it to draft, refine or explore ideas alongside human judgment.

On Claude’s consumer-facing platform, 52% of work-related interactions involved this kind of augmentation, where AI supports rather than substitutes human labor. Completely automated uses comprised the remainder. The balance has shifted slightly over time: augmentation accounted for a larger share earlier last year, but automation has steadily increased, particularly in enterprise settings.

“Data from November 2025 points to a broad-based shift back toward augmented use on Claude.ai: The share of conversations classified as augmented jumped 5pp to 52% and the share deemed automated fell 4pp to 45%,” noted the report. “Product changes during this period — including file creation capabilities, persistent memory, and Skills for workflow customization — may have shifted usage patterns toward more collaborative, human-in-the-loop interactions.”

Peter McCrory, Anthropic’s head of economics, told Fortune that adoption is moving unusually fast. “AI is spreading across the U.S. faster than any major technology in the past century,” he said. “In our last report that we put out in September, we documented that disproportionate use is concentrated in a small number of states. In this report, we see evidence that low-usage states are catching up pretty quickly.”

The impact, however, varies sharply by occupation.

In roles such as data entry or certain IT support functions, AI appears to be absorbing a growing share of core responsibilities — continuing a long-running trend toward automation. In other professions, particularly those involving complex judgment or interpersonal interaction, AI is more often used to strip away routine tasks, leaving workers to focus on higher-value work. For instance, radiologists can spend less time on documentation and more time on patient-facing decisions, while therapists can reduce administrative overhead and devote more attention to clients.

The study also finds that AI tends to deliver its biggest productivity gains on complex tasks — ironically, the same tasks where it is most likely to fail without human oversight. Claude can generate research summaries in minutes, McCrory said to Axios, but the usefulness of that output depends heavily on the user’s expertise.

“The most complex tasks that people use Claude for are the ones where Claude tends to struggle most,” he said. “Human oversight, direction and iteration is thus that much more valuable.”

That dynamic could complicate both for and against narratives about AI. Human involvement can act as a bottleneck, slowing productivity gains, but it can also serve as a force multiplier, allowing workers to scale their output rather than be entirely replaced by machines.

The findings were released in the backdrop of warnings from Anthropic’s own leadership — CEO Dario Amodei publicly cautioned in 2025 that AI could eliminate up to half of entry-level white-collar jobs and push unemployment into the double digits within the next few years. At Davos this year, Amodei said AI was “6 to 12 months” away from doing software engineers’ jobs.

The new data from his company may not contradict those concerns outright, but it does suggest that AI’s economic impact looks a bit more evolutionary and nuanced than completely apocalyptic — at least so far.

Anthropic also acknowledges its own incentives — the company has a commercial interest in presenting AI as transformative, and the tech is improving quickly. The patterns observed now may not hold even in the near future as models rapidly become more capable and avanced and as automation expands.

The index, though, offers an interesting snapshot of a labor market in transition at this moment in time. AI is increasingly getting embedded into everyday work, whittling jobs down into smaller tasks and redistributing effort between humans and machines. The job apocalypse may not be here just yet, but the nature of work is already shifting in ways that could be hard to reverse — or even meaningfully predict.