When 30-year-old Kim wraps up her full-time marketing job at 6 p.m., her day is only half finished. Three evenings a week, often including weekends, she rushes across Seoul to tutor middle and high school students in English.

“I’ve been tutoring for seven years,” she said. “With the 3 million won ($2,074) I earn from my main job, I feel like I’ll never be able to buy a house or start a family. Working one job just doesn’t seem enough for the future anymore.”

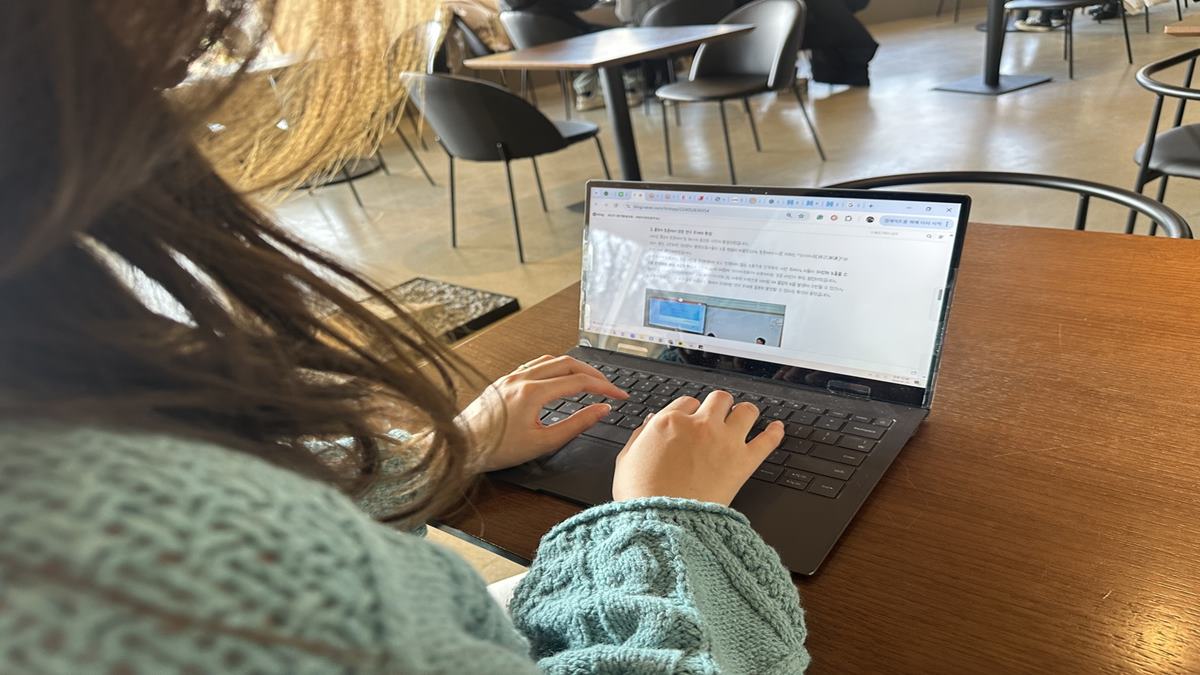

For 32-year-old Lee, a salesperson at a major conglomerate, nights are spent on his laptop, uploading and registering Korean beauty products on Amazon. The work is tedious and the platform’s standards demanding, often leaving him stressed. Still, he says he has little choice.

“After rent, groceries and the occasional meal out, there’s barely anything left to save,” he said. “This isn’t about ambition. It’s a necessity.”

Kim and Lee are far from outliers. Side jobs, once associated with freelancers or those between jobs, have quietly become a defining feature of young adulthood in South Korea.

Financial motivations, lack of trust in the traditional office structure, and even the desire to reinvent themselves or fulfill one’s personal dream are propelling the growing trend of “N-jobbers” — referring to those holding down more than one job.

Nearly half of Korean workers now report having a side hustle, according to a recent survey by job portal Incruit, with participation highest among those in their 20s (55.2 percent) and 30s (57 percent).

Survival strategies

Data backs the growing reliance on additional income. According to microdata from the Ministry of Data and Statistics, the number of workers with secondary employment, including both regular and temporary employees, reached 404,409 as of October 2025.

A survey of 728 adults conducted in December by short-term job search platform NewWorker also showed that 49.5 percent of respondents were engaged in some form of side work, nearly matching the 50.5 percent who said they were not. Among full-time office workers specifically, 48.4 percent reported having additional work beyond their main job.

Experts say the numbers likely underestimate the real scale, as many workers are hesitant to disclose secondary income sources to employers.

As the number of young Koreans taking on side jobs increases, so has the diversity in the side job market. Opportunities are tailored to digital skills or personal interests and are available online and offline.

Side jobs range from one-off paid appearances as wedding guests and private academic coaching to smartphone-based earnings, where an individual can earn a small amount of money by watching ads, browsing and physically walking.

With the widespread use of artificial intelligence, many are also seeking YouTube content production, blogging or running online stores to secure supplemental income.

“This diversification has been accelerated by social media, which functions as both a marketplace and a learning platform. Workers share tips on app-based earnings, digital sales strategies or content-creation know-how, encouraging more people to try low-barrier forms of additional income,” said a 34-year-old Lee Ji-won, who is earning an extra 1 million won by posting blogs.

“On Instagram, there are floods of posts about how to make money on the platform. Many who succeed publish books and become famous within the community,” Lee said.

Nearly half of Korean workers now juggle multiple income streams as daily expenses outpace earnings

When 30-year-old Kim wraps up her full-time marketing job at 6 p.m., her day is only half finished. Three evenings a week, often including weekends, she rushes across Seoul to tutor middle and high school students in English.

“I’ve been tutoring for seven years,” she said. “With the 3 million won ($2,074) I earn from my main job, I feel like I’ll never be able to buy a house or start a family. Working one job just doesn’t seem enough for the future anymore.”

For 32-year-old Lee, a salesperson at a major conglomerate, nights are spent on his laptop, uploading and registering Korean beauty products on Amazon. The work is tedious and the platform’s standards demanding, often leaving him stressed. Still, he says he has little choice.

“After rent, groceries and the occasional meal out, there’s barely anything left to save,” he said. “This isn’t about ambition. It’s a necessity.”

Kim and Lee are far from outliers. Side jobs, once associated with freelancers or those between jobs, have quietly become a defining feature of young adulthood in South Korea.

Financial motivations, lack of trust in the traditional office structure, and even the desire to reinvent themselves or fulfill one’s personal dream are propelling the growing trend of “N-jobbers” — referring to those holding down more than one job.

Nearly half of Korean workers now report having a side hustle, according to a recent survey by job portal Incruit, with participation highest among those in their 20s (55.2 percent) and 30s (57 percent).

Survival strategies

Data backs the growing reliance on additional income. According to microdata from the Ministry of Data and Statistics, the number of workers with secondary employment, including both regular and temporary employees, reached 404,409 as of October 2025.

A survey of 728 adults conducted in December by short-term job search platform NewWorker also showed that 49.5 percent of respondents were engaged in some form of side work, nearly matching the 50.5 percent who said they were not. Among full-time office workers specifically, 48.4 percent reported having additional work beyond their main job.

Experts say the numbers likely underestimate the real scale, as many workers are hesitant to disclose secondary income sources to employers.

As the number of young Koreans taking on side jobs increases, so has the diversity in the side job market. Opportunities are tailored to digital skills or personal interests and are available online and offline.

Side jobs range from one-off paid appearances as wedding guests and private academic coaching to smartphone-based earnings, where an individual can earn a small amount of money by watching ads, browsing and physically walking.

With the widespread use of artificial intelligence, many are also seeking YouTube content production, blogging or running online stores to secure supplemental income.

“This diversification has been accelerated by social media, which functions as both a marketplace and a learning platform. Workers share tips on app-based earnings, digital sales strategies or content-creation know-how, encouraging more people to try low-barrier forms of additional income,” said a 34-year-old Lee Ji-won, who is earning an extra 1 million won by posting blogs.

“On Instagram, there are floods of posts about how to make money on the platform. Many who succeed publish books and become famous within the community,” Lee said.

So what’s behind the surge?

Experts point to a disconnect between official inflation and lived reality. While consumer prices rose 2.1 percent last year — the lowest in five years — workers say daily expenses feel far higher.

Kim Sung-hee, director of the Institute for Industrial and Labor Policy, explained that growing expenses and stagnating income are driving even stable salaried employees into supplemental work.

“The pace of wage growth is not keeping up with the rise in living costs,” he said. “So more workers are adopting the ‘main job plus side job’ model as their default,” he added, predicting that the practice could lead to a long-term transformation in the labor landscape.

“At the same time, there has been a persistent increase in precarious employment. Society must rethink whether workers are being compensated fairly for their labor,” said Kim.

In fact, 82.5 percent cite the need for additional income, whether to cover daily expenses, save for emergencies or prepare for unexpected costs.

Lost faith in traditional career ladders

Experts say the trend also reflects a deeper shift in how young Koreans view work and careers. High inflation, stagnant wages and volatile employment conditions have eroded confidence in traditional career paths.

Surveys show young professionals increasingly reject the idea that climbing the corporate ladder is the only path to security.

According to last year’s survey by local think-tank 20s Lab on 850 office workers in their 20s and 30s, 36.7 percent of respondents said they do not wish to be promoted to a managerial position. Many cited the stress, workload and performance pressure associated with a promotion as reasons for their reluctance.

The apparent lack of desire for more authority at work was found in a 2023 survey of young workers by job-search platform Job Korea. Of the respondents, 54.8 percent said they do not want to be promoted to an executive position.

“Unlike past generations, young workers now know they can earn income outside the office through social media or e-commerce,” said Kim. “Taking on more responsibility at work is no longer seen as the best or only way to build a stable future.”

Seeking fulfillment

For some, the motivation behind side jobs goes beyond financial survival. A growing group of N-jobbers sees multiple jobs as a pathway to self-improvement, personal branding or long-term dreams.

“I realized the company isn’t everything and I needed to invest in myself,” said a 27-year-old professional in Seoul who runs a YouTube channel of some 27,000 subscribers. “My main job alone isn’t enough to prepare for the future. Through my side work, I’m building financial stability and gaining new experiences.”

But the rise of second and third jobs comes at a cost. Young N-jobbers now work an average of 58.7 hours per week, with some clocking nearly 97 hours, according to a report by the Korea Institute of Labor Safety and Health.

Experts warn this could worsen Korea’s already chronic burnout, deteriorate health and weaken family and social bonds.

“Trying to maximize income through multiple jobs reflects anxiety about falling behind in a society where economic power is paramount,” said sociology professor Heo Chang-deok of Yeungnam University.

“Yet long working hours are reducing productivity and straining relationships. We need to examine whether workers’ wages adequately reflect the value of their labor.”Source – https://www.koreaherald.com/article/10662196