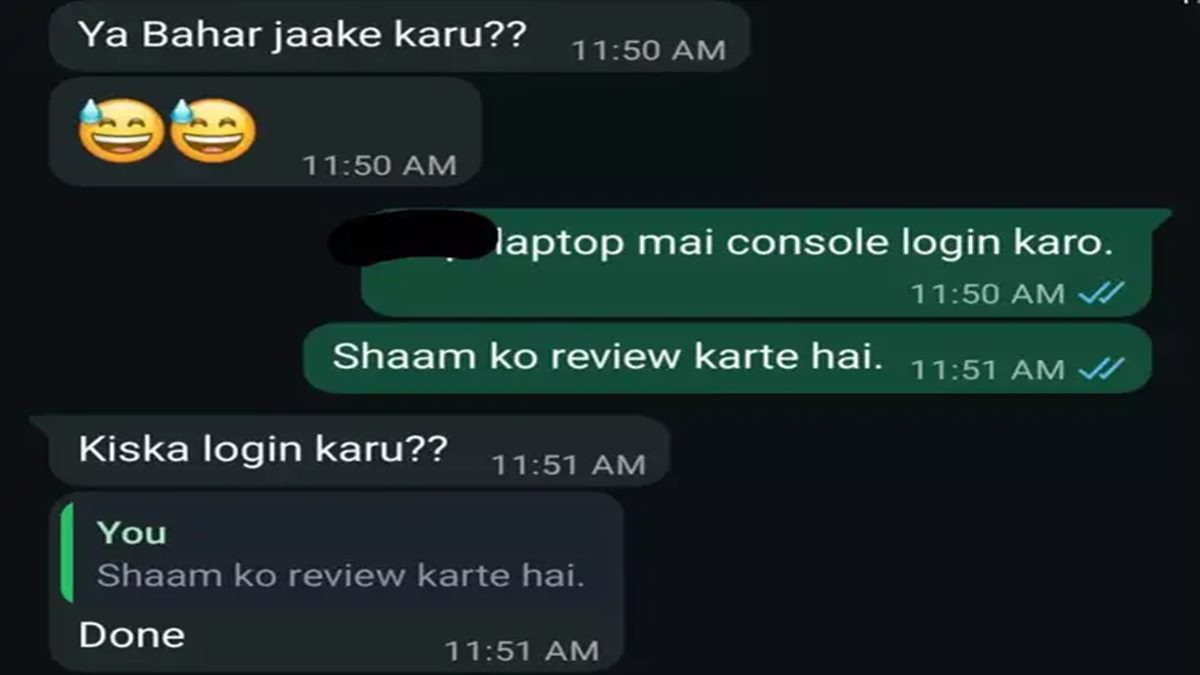

After a quick meal and a brisk workout, Ishan Sharma is downing a protein shake. By 10:30, he’s in office—getting the ring light set so it doesn’t reflect on his spectacles, tweaking the camera angle, while a whiteboard packed with thumbnail sketches and punchline hooks stands in a corner.

The day hums with energy: scripting reels, spitballing ideas, fielding calls with founders, venture-capital investors and corporate operators—and peddling his influence over 3mn followers on social-media platforms.

“Back in 2014, I read a news story about an IIT Roorkee student getting a Rs 2-crore package from Uber. That was a big moment for me and my dad…It looked flashy, aspirational,” says the 24-year-old who grew up in Pune (see interview, pg 54).

Over the next few years, he did the things every Indian teenager does to get into a top engineering college and made it to the Goa campus of BITS Pilani. His goal was within striking distance—it was a college that big tech firms like Google and Microsoft hired from.

Yet, Sharma dropped out of his electrical engineering course in his third year in 2022. His goal had changed by then—as the content-creation bug had bitten him.

“I was just waking up, eating and trying to retain as much information as I could,” he says. “It felt empty.”

Switching the Career Playbook

About 1,200km away from Pune, a 22-year-old in Jaipur who uses the moniker Zendria on social media has a similar story to tell. She dropped out of Indian Institute of Engineering Science and Technology, Shibpur—considered to be a premier engineering college—to focus on content creation full-time.

“I dropped out without informing my parents…They came to know two months later. I was pursuing computer science and was not able to deal with the stress of coding. So I quit,” she told her audience on YouTube after hitting the milestone of 1 lakh subscribers to her channel last year. Now she has racked up almost four times that number on the platform.

Across the world, a growing number of Gen Zs—defined as those born between 1996 and 2010 by management-consulting firm McKinsey—are turning their backs on college degrees and predictable careers, choosing instead to stake their futures on the creator economy. Until a few years back, millennials were rejecting the well-trodden career paths to start up their own businesses. Gen Zs are going a step further.

According to YouTube’s 2024 Culture and Trends Report, 65% of Gen Z individuals globally identify as content creators. The same report found that the phenomenon was wider among India’s Gen Zs—83% of them identified themselves as creators.

A handful of digital creators have achieved what used to be the domain of film stars and cricketers: acting offers, interviews with heads of state…

“Out of 10 students I talk to everyday, at least 6–7 express interest in becoming influencers or content creators. Interestingly, even students in professional fields like medicine or engineering come to us saying, ‘I don’t want to continue this.’ It’s not limited to teenagers—21-year-olds and even professionals with five years of experience are considering a switch,” says Swati Salunkhe, a Mumbai-based career counsellor.

“They see examples of influencer platforms and feel they can do it too—travel, eat, share opinions and make a business out of it,” she adds.

In India, several factors have converged over the past decade to shape this trend. First, a sharp drop in data costs after Reliance Jio’s 2016 launch brought hundreds of millions of Indians online. Second, TikTok’s intuitive interface made content creation simple and addictive.

When the app was banned in the country in 2020, it had already set the tone for a new style of storytelling—snappy and short. Instagram Reels and YouTube Shorts quickly filled the vacuum.

The tipping point was the pandemic when a lot of the Gen Zs were suddenly home and got unbridled access to the internet and smartphones. Many of the older Gen Zs were likely in the first year of their jobs. The rest—or the bulk of them—were in college or school. As their classrooms shifted to smartphones and laptops, even parents who were once hesitant with internet access for children had to budge.

Life Takes a Turn

And that’s when Gen Z took the plunge—what started as casual posting quickly turned into hours of filming, editing and studying algorithm patterns. For many, the transition from student to creator was almost accidental. Stuck indoors, starved for connection and saturated with screen time, they turned to content not just to consume but to express, experiment, and eventually, to earn big money.

“After the pandemic, the college asked us to return, but I couldn’t adjust to the environment. I had spent the previous couple of years at home focusing on my YouTube channel, learning new skills and building my marketing company. Returning to college meant attending lectures and focusing on things that no longer excited me. I felt like I had outgrown that space,” Sharma tells Outlook Business.

Something else was happening during the pandemic. For the first time, marketers were realising that Gen Z had become a significant cohort of consumers. Even if they were spending their parents’ money, they themselves were driving a lot of the purchase decisions.

Currently, Gen Z accounts for 46% of India’s total consumer spending, amounting to $860bn, according to a report by social-media platform Snapchat and management firm Boston Consulting Group (BCG). This demographic’s spending is particularly prominent in categories such as footwear, dining, out-of-home entertainment, and fashion and lifestyle.

“The thing is even if Gen Zs don’t earn enough to pay for a purchase at home like a car, a smartphone, a television set or an air conditioner, they are key to making the decision of what will be bought. It is increasingly more so today as almost every product in the household becomes more technologically connected,” says Renu Bisht, founder of management-consulting firm Datum.

The BCG report’s projections indicate that by 2035, Gen Z’s spending power will escalate to $2trn, with direct spending—money earned and spent by Gen Z individuals themselves—expected to reach $1.8trn. This growth suggests that by 2035, every second rupee spent in India will be driven by the wallet of a Gen-Z consumer.

So, brands want to catch ’em young. But they are not to be found on TV channels. As their elders infiltrate platforms like Facebook and X, these youngsters flee those spaces in search of newer platforms like Snapchat and Discord.

Experts say that as brands scramble to win the loyalty of Gen Z—the largest and most digitally native cohort—a significant chunk of advertising money is flowing into the hands of content creators. Just as ad spend once drove cigarette smoking in the post-war US or shaped household beauty standards of fairness in post-liberalisation India via TV commercials, today marketing dollars are underwriting the creator economy.

Followers and Fame

Take for example a teenage creator named Ayush. He had around 5,000 followers on Instagram until a couple of months back but unexpectedly shot to fame thanks to a quirky video that went massively viral. It centered around a humorous mispronunciation of croissant as ‘Prashant’—and the internet lapped it up.

The video racked up millions of views, making the youngster the talk of the town for weeks. It caught so much attention that Britannia embraced the trend and even renamed its croissant packaging to ‘Prashant’ for a limited duration. Since then, his follower count has jumped over 10 times while he has earned brand sponsorships with the likes of Netflix, Myntra and Phillips.

It is not easy for those like Ayush—who get a taste of virality in their teens—to be content with normal life. They want to make it bigger and better.

Ask Abhishek Verma—he has been there. Hailing from a village in Chhattisgarh, he dropped out of college a few years back to create music content on the platforms. Starting small, Abhishek had just one laptop and a digital audio converter. His first independently recorded track was “Gali Ka Ladka”—a song about rural life. It garnered over 1 lakh views and earned him his first income of Rs 2,500.

In June 2024, Abhishek moved to Delhi. “I felt like my growth had stagnated,” he says. He needed a bigger stage.

His village, Tulsi, is unlike most. Out of 4,000 residents, over 1,000 work in content creation, mostly on YouTube. But Abhishek sees a gap. “People create, but they don’t know how to generate revenue. No one teaches them how to build a business around their content,” he says.

In the big leagues, the money is dazzling. Top creators can command anywhere between Rs 2 lakh and Rs 10 lakh per branded reel, while mega-influencers rake in over Rs 1 crore per campaign, often spanning multi-platform tie-ins with everything from tech to toothpaste.

Moreover, a handful of digital creators over the past few years have achieved what used to be the exclusive domain of film stars and cricketers: acting offers, interviews with heads of state and invitations to the global stage such as the Cannes red carpet or the World Economic Forum in Davos.

Consider Prajakta Koli, a former radio intern who now sits across from Michelle Obama and Bill Gates in podcasts and stars in Netflix series. Or Kusha Kapila, who parlayed her Instagram sketches into an acting career in Bollywood, a judging spot on Comicstaan and a reported net worth of millions of dollars.

Then there are finfluencers like Sharan Hegde and Ankur Warikoo who sell courses, build apps and launch start-ups on the back of their online fame.

For Gen Zs watching from the sidelines, it presents an attractive idea of meritocracy—where a smartphone and an opinion might be all you need to escape your Tier-II town. It’s not just the promise of money, but the shape-shifting stardom that seduces them.

Ruopfuzhano Whiso, a 25-year-old skin-care and lifestyle creator from Nagaland with 1.75 lakh followers on Instagram, says she has her sights on the silver screen.

“There are no offers yet,” she admits, “but I’d love to explore acting. I have some plans in the pipeline and I hope something good comes my way.”

Her dream is to rule the box office like Deepika Padukone one day.

All That Glitters is Not Gold

With a population of over 1bn and more than 850mn internet users, it’s no surprise that as many as 4mn Indians now call themselves content creators, chasing virality across Instagram, YouTube and a constellation of short-form video apps.

But scratch the surface—and the fault lines become visible.

After getting his Master of Commerce degree from Gauhati University in 2019, Shubham (name changed) started working as a salesperson at a private-sector bank. As the pandemic hit a year later, he took to posting artwork online. As his following grew to over a few hundred and then a couple of thousand, he started getting enquiries to buy his sketches that were done in the Pattachitra style, an art form practised in eastern India. Also, due to his rising popularity, local consumer brands enlisted his services to market their fare on his page.

Dissatisfied with his sales job, Shubham quit. And took up content creation full-time while preparing for government jobs on the side at the insistence of his family. At the beginning it was great going for him—he rolled in more than the Rs 30,000 per month that the bank was offering, the engagement on his posts rose every few weeks and his friends were envious of the success. He also bought an iPhone on EMI so that his photos and videos looked better online.

But within a year or so, competitors emerged who copied the same style. As the novelty dropped, so did his pricing power and engagement on Instagram and YouTube. His follower count stagnated. And Shubham had to go back to the drawing board to plan his next career move from scratch.

“If you take a close look, you will find that no more than 1% of content creators make a significant income. Even within that elite group, most earn around Rs 5,000–10,000 a month. A lot of them might just be barter deals such as a creator promoting a smartphone gets to keep it,” says Shudeep Majumdar, chief executive of influencer-marketing agency Zefmo.

“The data might say that the creator economy is worth about $1.5bn, but the industry is as skewed as Bollywood. The top five stars corner 90% of the revenue,” he adds.

To illustrate this point, Majumdar says that his agency has 3 lakh creators on board of which only about 5,000 are active. Most of the others would have been partnered with for brand sponsorships once or twice.

As per data from influencer-marketing platform Kofluence, influencer-marketing rates vary widely based on platform and follower count. On Instagram, influencers with 1,000–10,000 followers typically earn Rs 500–5,000 per post, while those with 10,000–1 lakh followers can charge between Rs 3,000 and Rs 1 lakh. For creators with 1–10 lakh followers, rates range from Rs 50,000 to Rs 5 lakh and those with over 10 lakh followers may earn upwards of Rs 2 lakh per post.

Home and the World

Apart from promoting brands and products, another significant revenue stream for creators across the world are the platforms themselves—the likes of Instagram and YouTube pay them for attracting more eyeballs to their apps.

However, the platforms have realised that numbers don’t always tell the story; millions of views in India may not translate into money because of lower digital spends in the country, compared to developed markets. So, they have either reduced the payouts in the country or stopped it.

For instance, India’s creators on YouTube typically get around $1.5 for every 1,000 views—but it varies and can be higher depending on the content category and viewer demographics. Meanwhile, in the US, it could be anywhere between $8 and $12.

As such, compared to the US, the platform payout to creators in India is 1/10th. But there is a work around.

“If a creator is able to crack a global market like the UK, Australia or the US then they end up earning much more, even if they have a fewer number of views and a lower subscriber base. That’s the reason that some creators who’ve stuck to creating content in English or creating content without language barriers—such as art or music—have done well,” says Vipasha Joshi, a creator-economy consultant based in Delhi.

Interestingly, the Indian government has caught on to this strategy of exporting content and importing global engagement and is trying to leverage it through a $1bn creator-economy fund. It is organising a summit this month for the creator economy in Mumbai which will bring together top executives and investors from the global media and entertainment industry.

Meanwhile, Joshi contends it’s not just the Centre but also the states which have taken note of the explosion of young content creators and the potential of exporting it to the world. She recently conducted a workshop for the Kerala government on these lines and is in talks with Himachal Pradesh to create such programmes.

Fragility of Fame

When the government intervenes in an industry, especially with its money muscles, it gives the segment a fillip. But it also brings with itself heightened scrutiny.

Take for instance Ranveer Allahbadia who was one of the awardees to take a prize from PM Modi at the government’s creator awards last year. The young content creator from Mumbai had been doing podcasts with sports stars, film stars and top politicians. He was reportedly raking in crores of rupees annually from brand endorsements. But one misstep in a YouTube video a couple of months back—in which he made an unpalatable joke that did not go down well on social media—has brought his career to a screeching halt. Nobody knows if he will recover from the mess.

For creators, navigating their formative years under the weight of engagement metrics, the cost of relevance is often paid in mental health

Experts say that even if a content creator’s fame is not hit by a controversy, it will most certainly plateau at some point in time—as a result of their growth being stalled by the algorithms which seek to reward fresh faces.

“I don’t think content creation is a full-time career in the long term. The platforms themselves prefer newer faces…And fame is a very fragile thing. That’s something every creator should be aware of,” says Sharma who was recently enveloped in a controversy around his endorsement of certain courses.

In the gilded age of content, visibility is currency and the algorithms the gods. For creators, particularly Gen Zs navigating their formative years under the weight of engagement metrics, the cost of relevance is often paid in mental health.

Gen Zs suffer from worse mental health compared to other age groups, according to a 2022 survey by McKinsey. Further it found that negative effects of social media were particularly pronounced for Gen Zs who spend more than two hours a day on social media.

Another survey by affiliate marketing platform Awin the same year found that 72% of influencers cite constant platform changes as a leading cause of anxiety, while 78% of them felt burnt out.

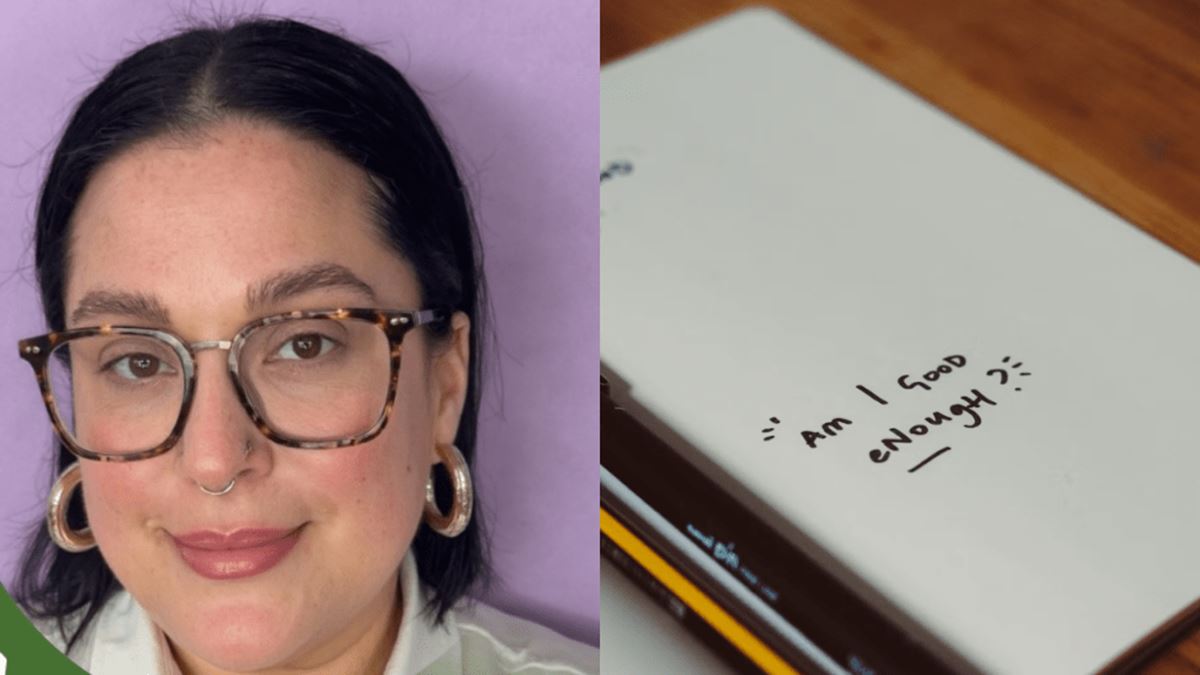

Divija Bhasin, 28, a Delhi-based psychologist, founder of mental-health organisation The Friendly Couch and a popular content creator herself with over 3 lakh followers on Instagram, describes the emotional calculus with unflinching honesty: “I have personally experienced this as a creator. It can trigger a lot of anxiety when you don’t grow your followers or don’t get the ‘same’ level of engagement you normally get. It makes you wonder what you’re doing wrong and you try to do everything you can to increase the engagement.”

On one hand, the creator economy promises freedom—no bosses, no fixed timings, no cubicles—exactly what Gen Zs often seek. But what it often delivers is a relentless hustle. There’s no clocking out. No watercooler chats. Just you, your metrics and the gnawing suspicion that if you disappear for a week, the internet might just forget you ever existed.

As Neha Cadabam, senior psychologist at Cadabam’s Hospitals, puts it: “You’re not allowing your brain to switch off, rest or take a break. It’s like you’re on a treadmill without a pause button.” For her Gen-Z clients, many of whom are creators, the symptoms are worryingly familiar: burnout, anxiety, social isolation and a persistent sense of identity crisis.

There have been extreme cases that ended in suicide.

On April 1, a 21-year-old influencer from Ahmedabad consumed poison and died. Reports indicate that he had grown increasingly anxious over his stagnant follower count that had remained stuck at 7,923. Despite putting in relentless efforts, Prateek, a fitness influencer, reportedly saw the lack of growth as a personal failure, leading him to this tragic decision.

Data from the National Crime Records Bureau report for 2022 also reveals that individuals aged between 18 and 30 years accounted for 34.6% of all reported suicides, making them the most vulnerable age group.

In the Indian context, there are family expectations as well. As Shubham, the Pattachitra artist from Assam, neared the age of 29 this year, he felt he was being compelled to make a tough decision.

“There was a lot of pressure from my parents to crack government job exams. I was trying to do it, but you can’t give enough time to both pursuits. If you are serious about content creation, it has to be a full-time job where you plan your posts days in advance, network with other creators to chalk out collaborations and assess the nitty-gritty of what works and what doesn’t,” he says.

While he has begrudgingly put the ring light away for now, the Gen Z in him still yearns to take another stab at making viral reels.