Earlier this year, China’s social media platforms were set alight by what had appeared to be a new workplace phenomenon: no overtime. Posts shared by corporate employees, which claimed that they had been forced to clock off and leave the office, became some of the most-read threads, gathering millions of clicks.

Chinese home appliance manufacturer Midea, for example, mandated its staff to finish work at 6:20pm in a bid to cut office bureaucracy, according to China’s state-run newspaper Global Times.

Others ordered their staff to shorten their overtime. Cai Min, an employee of Chinese drone-maker DJI, told The Economic Observer that his supervisor had told his team that they must go home at 9pm unless there were urgent tasks.

Cai and his colleagues had often had to work until midnight in the past, he said, but now most of them would leave by 9:10pm.

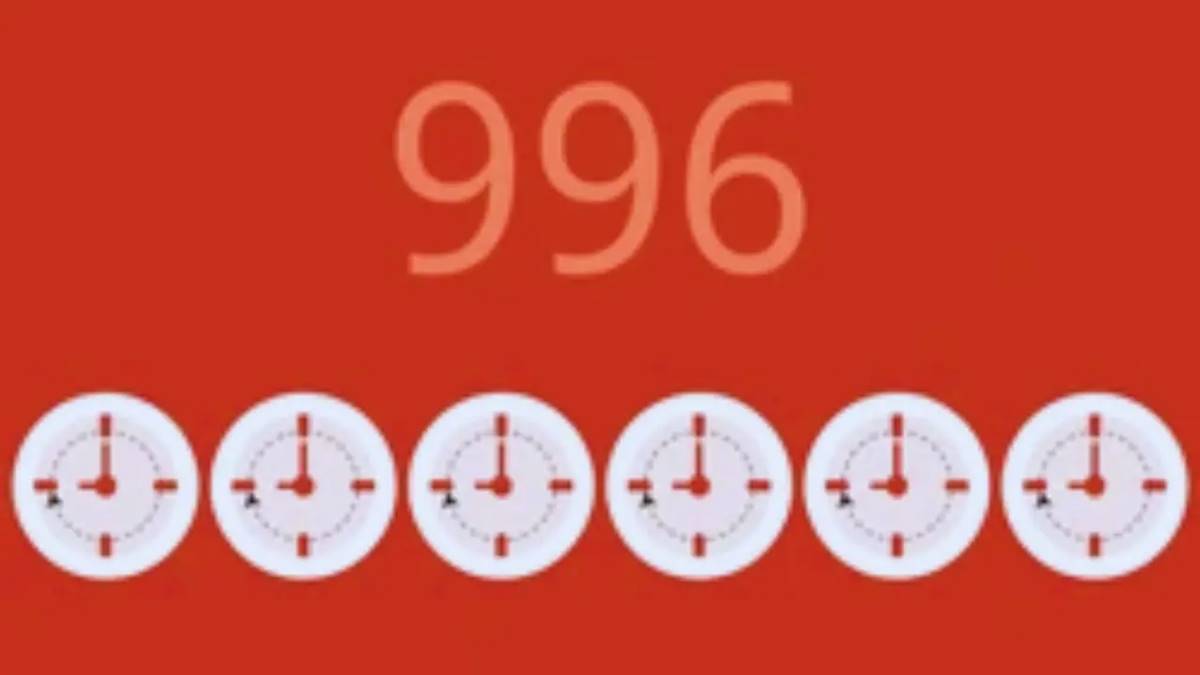

Many Chinese employees are expected to work a 72-hour week under the country’s gruelling “996” culture: 9am to 9pm, six days a week. The work style has been endorsed by some of China’s most successful entrepreneurs, including Alibaba’s founder, Jack Ma. But some critics have described it as labour exploitation, even modern slavery.

For the past few years, the Chinese government has attempted to stamp out “996”, including by outlawing it in 2021. That year, tech giants including TikTok parent company ByteDance and Tencent also tried to halt “996” after a 22-year-old woman at e-commerce firm Pingduoduo reportedly collapsed to her death on her way home from work past midnight.

But intense overtime has remained a common practice in China. The reasons are complex, including a lack of enforcement of the labour law and the country’s low minimum wages, according to researchers and executives interviewed for this report.

Long hours can have a range of negative effects on employees, including their health, job performance and work-life balance.

According to China’s labour law, an employee’s legal work length should not exceed eight hours a day and 44 hours a week. The law also caps their overtime at an hour a day – or three hours if their health is ensured – and 36 hours a month. All of these parameters are aligned with the recommendations of the International Labour Organization (ILO).

Even though the law is clear, the reality can be very different. During the first five months of 2025, Chinese people worked an average of 48.5 hours a week, according to official figures.

“I work more hours than ‘996’ every week. I feel very, very tired,” says a director of a company in the renewable power industry in China, who requests anonymity. He says his work hours are flexible, but he has to put in more than 12 hours a day – without overtime pay – if he wants to meet his sales target and get a bonus. “My bonus accounts for 50% of my monthly salary,” he says, adding that he works those extra hours voluntarily.

Long hours are often driven by China’s competitive office culture. Some employers impose aggressive performance targets on their staff, says Joyce Cheng, managing director of Hong Kong-based Sissin Consulting, which provides cross-culture communications between Chinese and European companies.

On the other hand, some employees also hope to show willingness to work hard and increase job security by taking on extra hours, she notes.

“Many Chinese employees are desperate to succeed or need to preserve their incomes to sustain more aspirational lifestyles, so there are enough people in the workforce who will persist with these working hours,” says London-based Oliver Pearce, managing director of communications advisory Corporate Perspectives, who worked in China for 15 years.

But there are also many wider social factors. China’s low minimum wages is one of them, says Sun Xin, a senior lecturer in Chinese and East Asia business at King’s College London. In Shenzhen, a tech hub bordering Hong Kong, the legal minimum wage is 2,520 yuan ($352) a month for full-time workers, much lower than its citizens’ average per-capita spending, which stood at 4,284 yuan ($598) a month last year.

“For some people, if they only work the hours defined by law, they will not be able to support themselves,” Sun says. There have been reports of factory workers demanding their supervisors give them overtime to earn more money.

The lack of proper labour law enforcement adds to the challenges. There is no independent trade union in China to protect workers’ rights and local governments tend to side with companies in court cases because of their joint interest, Sun notes.

Some researchers believe the core reason behind long hours is linked to Chinese workers’ low productivity. Output per worker in China is significantly lower than those in advanced economies, but many Chinese companies aim for high output and strong growth, according to Wang Zichen, a research fellow at the Center for China and Globalization, an independent think-tank in Beijing.

Improving productivity through investment and technological innovation is difficult and slow, but “extending working hours is a much easier and more immediate option,” he explains.

China’s recent drive to tackle “996” was particularly vigorous: there were even special TV programmes for it. For 10 weeks on Saturday nights, a prime-time talk show, simply called “Overtime No More”, invited celebrities, comedians and young workers from all walks of life to discuss their tactics. Topics ranged from how to say “no” to overtime requests to whether one should reply to their boss’s messages after work.

Hao Nan, a research fellow at the Charhar Institute in Beijing, says the campaign was partly a response to a regulation introduced by the European Union (EU) to ban products made with forced labour in the bloc.

The EU Forced Labour Regulation, which kicked in late last year, refers to the ILO’s standard of identifying forced labour, and that includes “excessive overtime” as one of the indicators. It will be officially applied to companies selling goods in the bloc in December 2027.

“China’s efforts to shift away from its overwork-driven culture reflect its attempts to align with EU standards, enhance worker wellbeing and diversify its economic relationships,” Hao wrote in an analysis.

Other researchers have different theories. Wang of the Center for China and Globalization sees no direct link between the two. “Even if the EU Forced Labour Regulation were enforced rigorously, it would likely target alleged labour abuses in specific regions, such as Xinjiang,” he explains. “It would not – and realistically could not – be applied to white-collar tech workers in major cities, who are not legally coerced into working long hours.”

The ILO has 11 indicators of forced labour, which also include restriction of movement, physical and sexual violence and others.

But indicators don’t mean that if there is excessive overtime, there is always forced labour, says Johannes Maximilian van Lingen, a Germany-based independent consultant of corporate human rights and sustainability due diligence with a focus on China.

“It only means excessive overtime can be an indication that there might be forced labour, but you have to draw a bigger picture to actually assess the situation, including whether the overtime is voluntary or not,” says van Lingen.

“When we talk about mandatory clock-off and, in a broader sense, a shift in working culture in China, we are usually not talking about people being forced to work overtime by penalties, threat or other measures,” he says.

According to the ILO, excessive working hours is an indicator of forced labour, but “whether or not a specific situation of excessive working hours amounts to forced labour will depend very much on the facts on the case”.

The organisation adds: “As a rule of thumb, if employees have to work more overtime than is allowed under national law, under some form of threat (e.g. dismissal) or in order to earn at least the minimum wage, this amounts to forced labour.”

Sun believes the real reason behind the clock-off trend is China’s recent effort to eliminate what is known by the buzzword “neijuan”, intense and excessive competition in a society that prevents it from developing healthily.

This is seen in the intense price wars in several of China’s key industries, such as solar panels and electric vehicles.

China’s central government pledged to address the issue in March. “That has led many companies to pay more attention to their corporate policies and employment practices,” Sun says.