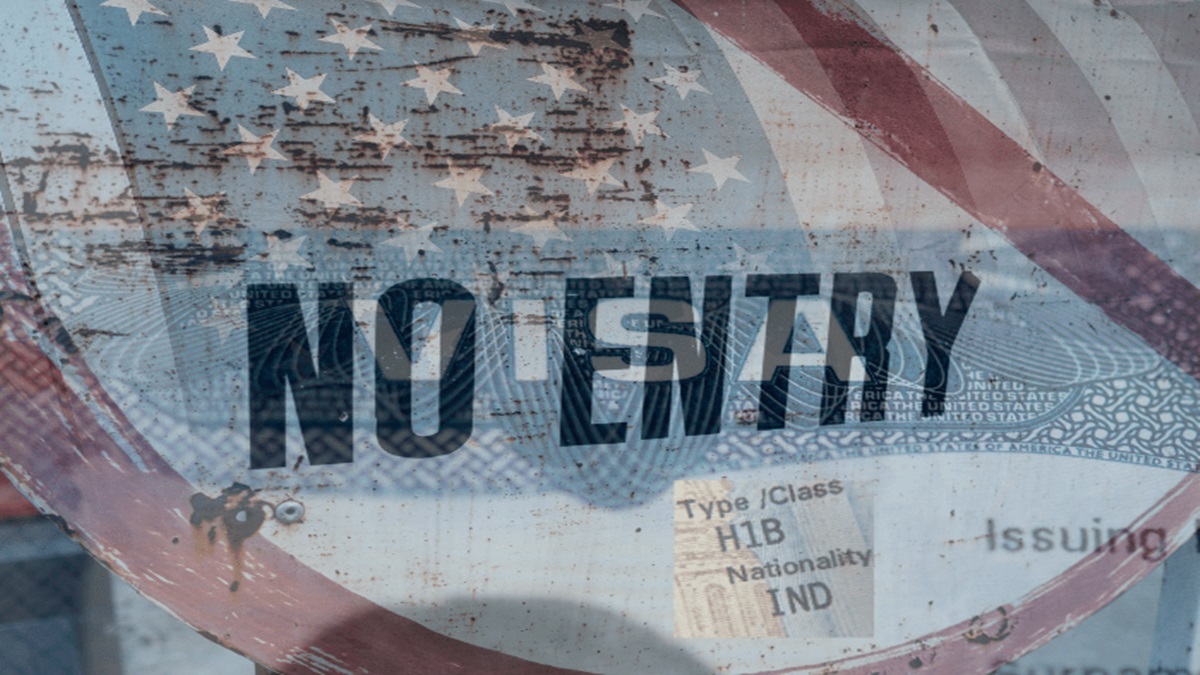

Last week in this column, I wrote about The Great Realignment — the slow but inevitable reshaping of India’s job market from the old IT services model to a more balanced future, anchored by manufacturing and home-grown product innovation. A few days later, the United States added a fresh twist to that story. Washington has hiked fees for the H-1B visa, the single most important ticket for Indian tech workers to enter the American economy.

The move has sparked anxiety in India’s IT corridors. For decades, the H-1B has been the symbol of ambition, a golden bridge between India’s engineering colleges and Silicon Valley’s cubicles. To raise its cost feels like yet another door closing, another narrowing of the Indian dream.

And yet, look beyond the immediate dismay, and a paradox emerges. What if the H-1B squeeze proves to be a boon in disguise? What if, by making it harder and costlier to send Indian workers abroad, the US is inadvertently pushing global innovation to relocate to India instead?

The visa shock that shook India’s IT

US President Donald Trump’s imposition of a $100,000 fee for new H-1B applications has sent shockwaves through an industry where Indians received 71 per cent of approved H-1B visas in 2024. Investors have already begun shedding shares of IT outsourcing firms including Infosys, Tech Mahindra, Wipro, HCL Technologies and Tata Consultancy Services. The panic is understandable—India sends more skilled workers to the US than any other country, making this policy change particularly devastating for the IT sector.

For too long, India’s IT success has been tethered to the fortunes of the H-1B. Every year, companies shipped thousands of engineers to the US to fill skill gaps in coding, testing, or systems integration. It created wealth, global exposure, and an aspirational middle class. But it also entrenched a model built on labour arbitrage rather than intellectual property—a dependency that always carried inherent vulnerabilities.

“India is no longer just the world’s back office—it is where the future is imagined, designed, and tested.”

Today, that model is under strain from multiple directions. Clients want AI, automation, and cloud-first solutions—not armies of coders. US policymakers, meanwhile, are less willing to subsidise a visa pipeline that outsources jobs. The fee hike is only the latest reminder that this dependence is unsustainable.

GCCs: From back office to innovation engines

Enter the Global Capability Centre (GCC). Once dismissed as offshore “back offices,” these hubs have transformed into engines of high-value work. India today hosts over 1,700 GCCs, employing close to 1.9 million professionals directly. Collectively, these centres generated $64.6 billion in revenue in FY24, according to Nasscom. By 2030, the GCC industry is projected to touch $99–105 billion, employing between 2.5 and 2.8 million people.

The depth of India’s GCC ecosystem is particularly telling: more than 480 mid-market GCCs—firms smaller in scale but often nimbler in experimentation—already employ over 210,000 professionals. Together, they form an ecosystem that is both broad and resilient, representing a fundamental shift from cost arbitrage to strategic core operations.

Consider Mercedes-Benz Research and Development India (MBRDI) in Bengaluru. When established in 1996, it was a modest extension of the German engineering base. Nearly three decades later, MBRDI employs more than 8,500 professionals across Bengaluru and Pune, making it one of the company’s largest R&D hubs outside Germany. Engineers there work not on routine tasks but on autonomous driving, electric mobility, connected vehicles, advanced driver assistance, electric drivetrain software, and AI-powered safety systems—technologies that define the next decade of mobility.

“Restrictions could redirect talent toward domestic innovation, creating IP India can claim as its own.”

Microsoft’s India Development Centre has been integral to flagship products such as Azure and Teams and is known to hire the best of the lot—engineering graduates from IITs, IIITs, and NITs for starting salaries as high as Rs 45 lakh per annum. The amount does include joining bonuses etc, but even then it is on the higher side.

Goldman Sachs’ Bengaluru office, once back-end support, is now a hub for risk modelling, AI-driven trading, and consumer banking platforms. Walmart Global Tech India employs over 9,000 people, building e-commerce platforms for Walmart’s worldwide operations. J.P. Morgan’s India GCC, with more than 50,000 employees, runs trading systems and analytics that power Wall Street.

Far from being auxiliary, these centres are becoming indispensable. They are no longer passengers in the global economy; they are pilots.

Why the visa hike strengthens the case for India

Here lies the irony. Every dollar added to the cost of relocating an engineer to the US strengthens the argument for building teams in India instead. The economics tilt decisively toward bringing the work to India, not Indians to the work.

“The H-1B squeeze may be the catalyst that turns India from exporting coders to creating global innovators.”

India’s advantages are compelling: a vast STEM talent pool, a start-up ecosystem buzzing with AI ventures, improving infrastructure, and government incentives for advanced research. For a global firm, it is not just cheaper but smarter to scale innovation in Bengaluru or Hyderabad than to navigate US visa politics and absorb the $100,000 fee burden.

The pandemic was a watershed moment that accelerated this recognition. It tested resilience and accelerated digitalisation. Whilst global businesses struggled to keep operations intact, India’s GCCs demonstrated adaptability, often driving global continuity. This resilience has not gone unnoticed. Companies that once saw India as an auxiliary arm now see it as mission-critical.

As Nasscom and Zinnov note, the talent base is also maturing. India’s GCC workforce is no longer just execution-heavy—it is leadership-rich. Increasingly, CXOs with global portfolios are being placed in India, a sign of growing trust and strategic importance.

“GCCs have evolved from execution-heavy units to leadership-rich hubs driving global mandates.”

From service provider to IP creator

The broader impact is cultural and represents a fundamental shift in ambition. The H-1B model encouraged India’s best talent to view success as working for American companies. Restrictions could redirect this talent toward building domestic innovation ecosystems and product companies rather than remaining perpetual service providers.

For the first time in decades, India is building intellectual property it can claim as its own. The rise of AI product companies provides compelling evidence. Perplexity AI, co-founded by Indian-origin engineers, is challenging Google in search. Freshworks, Zoho, and Postman have already shown the world that Indian companies can lead in enterprise software. Generative AI is spurring a wave of startups in healthcare, education, logistics, and agriculture, solving uniquely Indian problems with global implications.

This represents more than economic diversification—it’s about recalibrating national ambition. When engineers in Bengaluru design the future of mobility or create AI products that rival Silicon Valley’s best, they are no longer coding someone else’s vision. They are shaping their own, building companies that compete globally rather than merely delivering services to global companies.

The brain drain that saw India’s brightest minds emigrate also meant their wealth creation benefited other economies. Keeping talent domestically could accelerate India’s startup ecosystem and venture capital development, creating a virtuous cycle of innovation, investment, and intellectual property creation.

The forced innovation imperative

The H-1B restrictions represent a form of forced innovation that could prove transformative. Indian IT companies have become comfortable with the low-risk, high-volume outsourcing model. Visa restrictions force them to evolve toward higher-value services, R&D, and product development—areas where they’ve historically underinvested.

Companies may finally prioritise India’s massive domestic market rather than viewing it as secondary to Western clients. This could drive innovation around India-specific problems in healthcare, education, agriculture, and governance—sectors where India’s scale and unique challenges could generate globally relevant solutions.

Historical precedent suggests this disruption-driven innovation can succeed spectacularly. Countries like Israel and South Korea built innovation economies partly because external circumstances forced them to develop domestic capabilities. China’s tech giants emerged partially because foreign platform restrictions created space for local alternatives.

Ripple effects across talent and start-ups

The expansion of GCCs and product innovation has ripple effects throughout the economy. Salaries are higher, demand for advanced skills surges, and universities are forced to modernise curricula. A local ecosystem of vendors, start-ups, and R&D collaborations flourishes around these centres.

However, significant risks remain that could undermine this transition. Many H-1B aspirants are trained specifically for roles that may not exist domestically. Retraining entire cohorts for local market needs requires time and substantial investment that neither government nor industry may be prepared to provide.

Infrastructure bottlenecks—unreliable power, crumbling urban transport—could erode India’s cost advantage just as global demand peaks. Talent attrition, already rampant in Bengaluru and Hyderabad, could worsen as more firms chase the same pool of skilled engineers. Without deliberate investments in reskilling and university-industry partnerships, India risks a talent crunch precisely when opportunity is greatest.

Capital flight represents another danger. Multinational companies may simply shift operations to countries with easier access to American markets, taking both jobs and investment elsewhere. India’s venture ecosystem, whilst growing, still lacks the depth and risk appetite of Silicon Valley. Redirected talent may struggle to find adequate funding and mentorship for ambitious projects.

The immediate impact includes job losses, reduced foreign exchange earnings, and sector instability that could take years to recover from. The “boon in disguise” scenario requires deliberate action from policymakers, educators, and industry—not just market forces.

A turning point for India’s tech ambitions

So, is the H-1B visa fee hike a threat or an opportunity? Seen narrowly, it represents another restriction on mobility, another loss of opportunity for individual engineers. But viewed within the broader arc of India’s economic evolution, it could serve as a catalyst.

By making it harder and more expensive to send Indians abroad, the policy accelerates the relocation of innovation itself to India. The US may close its doors, but global companies are opening labs, R&D centres, and product hubs in India. That shift could matter far more than the number of Indians who manage to work in California or New Jersey.

The real prize is not how many H-1Bs are stamped each year, but how much intellectual property is created on Indian soil. For companies like Mercedes-Benz, India is no longer just “the world’s back office.” It is where the future is imagined, designed, and tested—before it hits the roads of Stuttgart, Shanghai or San Francisco.

The next frontier of GCCs will be about co-creation, leadership and ownership of global mandates. India, with its scale, skills and adaptability, looks poised to remain the epicentre of this transformation.

If India seizes this moment—through supportive policies, educational reforms, and a willingness to embrace risk—the visa fee hike will not be remembered as a setback, but as a turning point. The moment India moved from exporting coders to building global innovators, from serving the world’s technology needs to creating the technologies the world needs.

The optimistic scenario assumes India will rise to this challenge. The pessimistic view suggests talent will simply migrate to other countries with easier visa pathways, leaving India with neither the benefits of domestic innovation nor international opportunities.

Which scenario unfolds depends on choices made in the coming months by policymakers, educators, and the technology industry itself. The H-1B squeeze has created the conditions for India’s innovation dividend. Whether that dividend pays out depends entirely on what India does next.