The recent anecdote of an IIT Gandhinagar graduate in Gurugram sparked a viral conversation that distils the existential crisis of the modern worker, revealing he wasn’t staying late out of ambition or fear of a toxic boss, but simply to avoid city traffic. This personal scheduling “hack” exposes a profound truth: for millions, the real villain isn’t the job, but the non-productive, energy-draining commute. The question is no longer if we should embrace flexible work models, but how we can use them to fundamentally redesign the relationship between our time, our cities, and our well-being. Looking at the broader picture, the hybrid work model does reduce the rush on roads, although not completely. In contrast, it significantly reduces accurate peak hour volume, and it often creates a smaller, later surge, shifting the congestion window rather than eliminating it entirely. The real liberation comes from the flexible shift, which allows the employee to trade the stressful, cognitively draining two hours of gridlock for two hours of self-investment, whether that’s sports, reading, or personal growth. Psychologically, this is a massive win, as minimising minor, daily frustrations like traffic congestion, following the principles of Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman, preserves cognitive bandwidth and enhances decision quality. Companies must realise that this “stranded time”—the gap between work finishing and the traffic clearing—is an opportunity to boost an employee’s mental well-being and subsequent productivity.

To capitalise on this reclaimed time, organisations need a radical shift in how they view the office, transitioning it from merely a processing centre to a hub for life integration. Current practices indicate that few workplaces permit employees to spend time on campus after working hours for personal projects or well-being, often requiring bureaucratic hurdles. This needs to change, with companies investing in office infrastructure that facilitates well-being, such as on-campus gyms, quiet reading rooms, or shared facilities for sports, alongside clear late-access policies that encourage employees to utilise the campus as a safe, conducive “third space” until traffic subsides. Regarding urban planning, full de-urbanisation (moving offices out of major metropolitan hubs entirely) is logistically complex and often undesirable for specialised talent. A more effective solution is decentralisation, which involves establishing smaller, full-featured satellite offices in suburban areas to bring the workplace closer to where people live and distribute the traffic load.

However, the promise of flexible shifts is counterbalanced by significant managerial challenges, which demand a shift in management paradigm from measuring input, such as hours logged, to measuring output through clear Key Performance Indicators. Task delegation must become asynchronous, relying on robust project management tools rather than constant verbal check-ins. A key challenge is the psychological effect of a “sense of presence” on decision-making, as many people believe that spontaneous, high-quality decisions occur only when everyone is physically present. While synchronous, high-stakes brainstorming may benefit from physical presence, routine, data-driven decisions are often made more efficiently remotely. The significance of spending a specific amount of time at the workplace versus elsewhere is tied to whether the task requires co-located synchronous interaction; if not, management must redefine the office’s purpose as a hub for connection and culture, rather than just individual work. It will also not be possible for all professions to adopt the same level of flexibility; services like IT and finance are highly adaptable, while academics can hybridise research but require presence for teaching and labs, and manufacturing is the least flexible, demanding employees on-site for core roles like assembly and quality assurance, though support roles can flex.

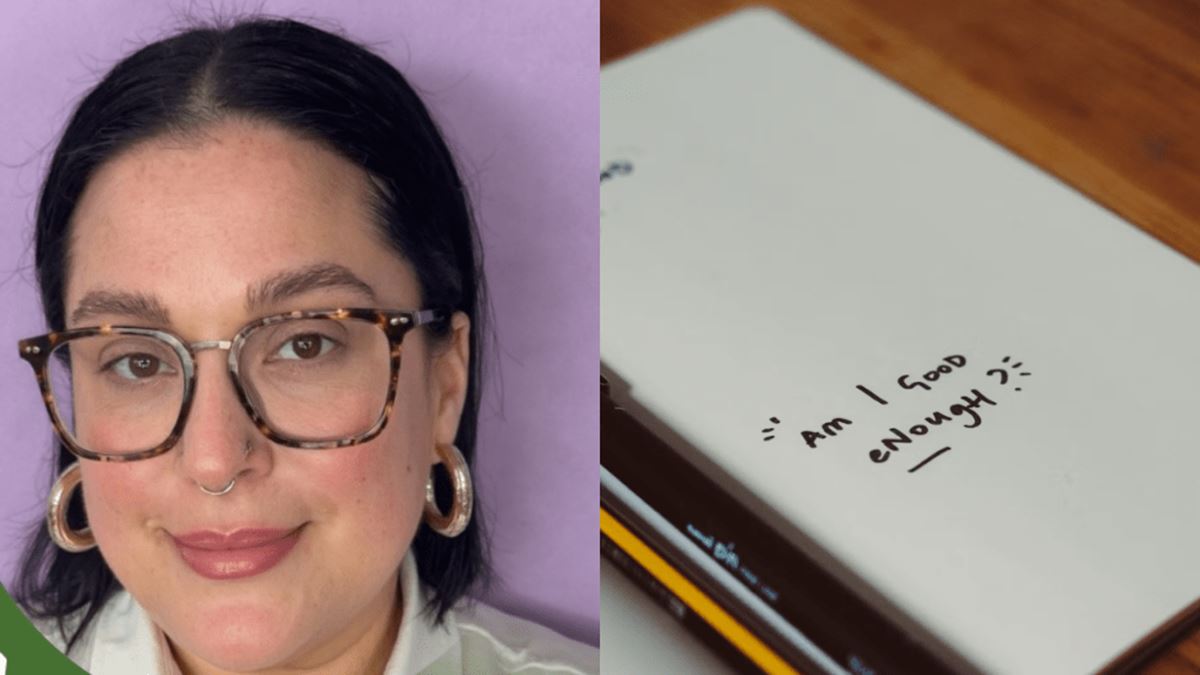

The advantages of flexible shifts for employees include improved well-being, reduced commuting stress and costs, and better work-life integration. However, disadvantages include potential social isolation, difficulty “switching off,” and the risk of being overlooked for promotion—the “out of sight, out of mind” effect. For the organisation, the advantages are access to a broader talent pool, reduced real estate overhead, and higher employee retention. Conversely, the disadvantages include coordination complexity, potential security risks, and difficulty in managing performance due to a lack of trust. To realign these dynamics, a new social contract built on radical trust and transparency is paramount. Organisations must invest heavily in collaboration technologies and train managers to lead remote and hybrid teams based on outcomes, not activity. The story of the IITian is a powerful metaphor for millions who feel their time is stolen by outdated infrastructure; the flexible work model is not a temporary pandemic fix, but a permanent productivity hack and a necessary step toward building smarter, less-congested cities and more human-centric careers by ensuring we stop sacrificing our mornings and evenings to the car and start reinvesting that time in ourselves.