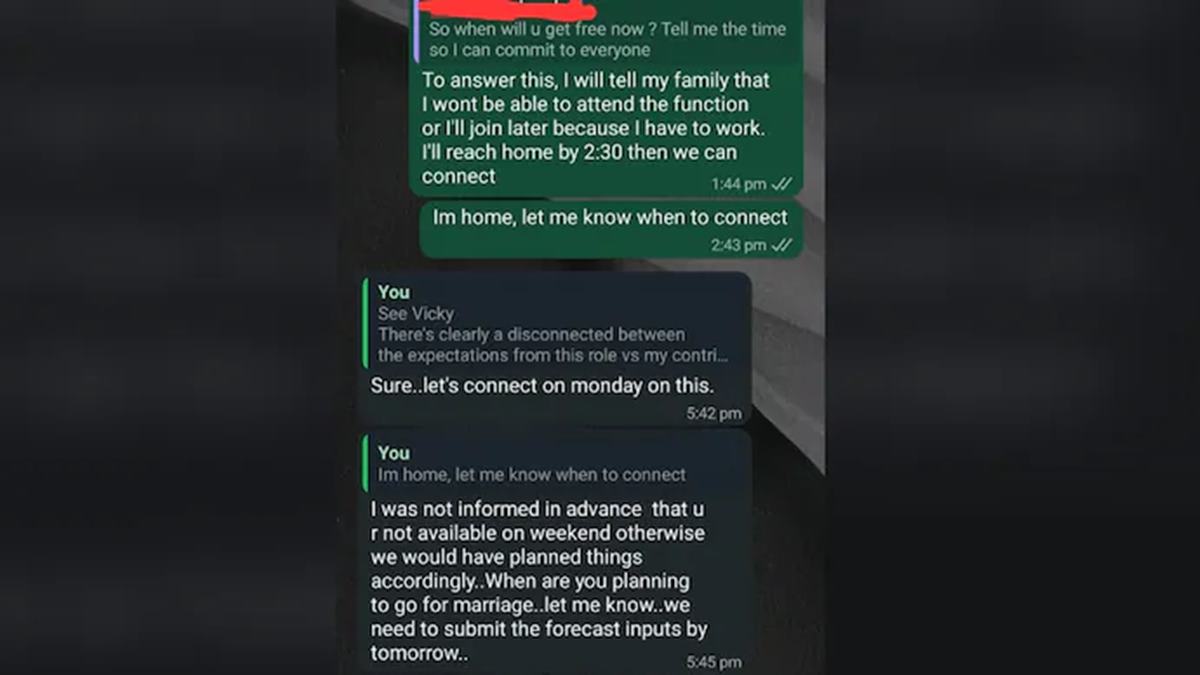

Sven, a sales leader, received a call from a major customer who was furious. Their order arrived late, the product was damaged, and to top it off, their invoice didn’t reflect the volume discount promised in the quarterly newsletter.

Sven wasn’t quite sure what to do. He’d need to involve other departments to resolve the problems, but there was a lot of organizational red tape. Plus, recent layoffs and economic uncertainty had him paranoid about making a mistake. Sven decided to bring the problem to my client Laura, his manager and the organization’s chief revenue officer.

Laura listened attentively as Sven waded through the details. She asked, “What support do you need from me?”

“Could you reach out to the customer?” Sven asked.

Laura knew Sven was capable of managing the problem, but she didn’t want him to feel unsupported or dismissed. So, she agreed, adding item #143 to her daily to-do list.

In that moment, each felt a sense of temporary relief: Sven was relieved that Laura was going to solve this, and Laura was relieved that Sven felt supported in a rough moment. Yet, over time, the dynamic repeated itself, and relief faded. Laura was burning out fast, Sven felt powerless with his own customers, and results were starting to dip.

It’s a pattern I see repeatedly in my coaching practice, and one that’s been well documented in research on learned helplessness and decision fatigue. This dynamic creates decision-making bottlenecks, diminishes team ownership, and accelerates managerial burnout.

Many leaders today are struggling to balance the aspiration of being a supportive leader with the reality of being overwhelmed. If you find yourself wishing problems would stop landing on your desk—even though you care deeply about the people bringing the problems—you’re not alone.

Abandoning compassion is not the answer. You don’t have to slam your door, or tout the (terrible) adage of “Don’t come to me with problems, come to me with solutions!”

Through my years of coaching leaders through decision overload and team dependency, I’ve identified five questions leaders can use to remain accessible, coach your team to problem-solve independently, and safeguard your time. My clients across industries report consistent results: When they shift from problem solving to using these five questions, their teams step up.

What have you tried?

Asking this question doesn’t suggest you’re not available to support. Instead, it signals that you expect initial effort, or at minimum, some brainstorming to have occurred prior to looping you in. This verbiage is a gentle reminder to employees that they have authority to act.

The first time you ask this question, you may be met with an awkward silence or “Uh, nothing yet.” After the first few times, your team will learn to anticipate the question, start thinking ahead about solutions, and pause before passing problems upward.

A director of tech ops I coached, Taylor, was frustrated that 1:1s with his employees had devolved into weekly venting sessions about organizational dysfunction. To make matters worse, most of these meetings resulted in a laundry list of follow-ups and problem-solving tasks for Taylor to handle alone.

When he began consistently asking, “What have you tried?”, the tone of 1:1s shifted, and so did the outcomes. Within a month, his team started showing up with partial solutions instead of raw problems. Conversations became more focused, follow-through improved, and the team started solving smaller issues on their own, without reflexively handing them to Taylor.

What—or who—is getting in the way of tackling this?

If your employee hasn’t been able to tackle a problem, they should at least be able to identify why. Whether it’s budget, time, or signoff, get to the root of what’s stopping them from solving it. Removing the obstacle is typically more efficient for you, the leader, than taking ownership of the entire problem.

This question also helps you identify themes of the challenges that land on your desk. Is it typically a signoff issue that’s getting in the way? Is it an unresponsive department or problematic vendor? Identifying recurring blocks enables you to build sustainable solutions that don’t depend on your constant involvement.

What support do you need?

The traditional question of “What support do you need from me?”—as my client Laura asked Sven—is a well-intended leadership sentiment, but it can unintentionally limit the number of potential support avenues. Support is general. It doesn’t have to come from you, the leader. It could also come from another leader, a fellow teammate, an adjacent department, or an external resource.

When employees feel comfortable seeking help broadly, problems get solved faster, and teams build connectedness that doesn’t depend on direct manager involvement. Encourage your team to think bigger about the resources they can tap into.

What would you do if you were in my seat?

When you solve problems for your team, they often don’t see the effort you put in—staying late, sending follow-up emails, navigating politics, and weighing trade-offs. This results in:

- No appreciation for the person doing the solving

- No skill-building for the person who handed it off

Asking this question prompts your employee to carry some of the intellectual load of problem-solving. You’re asking for their insights and inviting them into the decision-making process.

I recently coached a customer success leader who was completely underwater, fielding hourly escalations. When she started asking her team, “What would you do if you were in my seat?”, she saw a number of benefits: Her team started bringing forward more thoughtful ideas; they became more patient when problem-solving took time; and they stopped handing her the same problem twice. They saw firsthand what went into solving the issue, and they began to learn how to do it themselves.

A longitudinal study of more than 1,000 employees across 90 teams found that leaders who engaged their teams in decision-making and shared problem-solving saw significant increases in both team effectiveness and individual work engagement over time.

Is there anything else I should know?

Sometimes, the only reason a problem is on your desk is because your employee didn’t want you to be surprised by it.

Thanking the employee and then asking “Is there anything else I should know?” validates an open line of communication while leaving the active solutioning to the teammate. They can still ask you for help, but it’s on them to be direct with the request.

Differentiating between awareness of a problem and ownership of a problem is critical. Fend off the temptation to jump into the weeds. Unless specifically requested, don’t assume action on your part is necessary.

. . .

There isn’t a self-care checklist, meditation, or brain hack that’s going to make an inroad at chronic managerial overwhelm. To bring your best self to the most important moments, the volume of tasks must decrease.

The more you use these five questions, the less you’ll have to ask them. Empowering your team to own their role is a gift to everyone. Only with breathing room can you be a fully compassionate leader. Only when employees feel empowered are they able to independently drive results.

Source – https://hbr.org/2025/07/stop-solving-your-teams-problems-for-them