India’s growth reflects jobless productivity: output and profits rise, but employment and progression lag, fuelling economic unease.

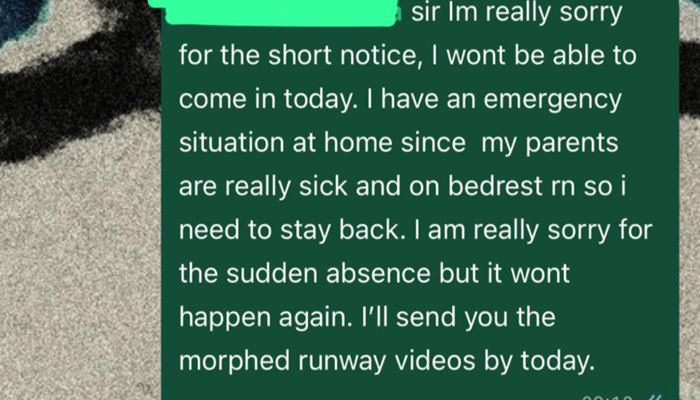

A young engineering graduate in Hyderabad describes his job search with weary precision. “There is work,” he says, “but not a career.” After months of applications, he has two offers: a short-term contract in logistics and a commission-based role selling financial products. Neither offers structured training, stability, or a credible path upward. “My parents had fewer options,” he says, “but more certainty.” The economy is expanding. His future feels provisional.

India does not lack work. It lacks work that accumulates skills, security and progression. That is the jobs problem rarely named in public debate.

When Strong Numbers Hide Weak Jobs

Public discussion oscillates between unemployment rates and headline growth, as if the two moved in tandem. But India’s challenge is not simply how many people are employed. It is what kind of jobs are being created, at what scale, and with what prospects. The latest Periodic Labour Force Survey places headline unemployment at a manageable 3.2 per cent. Yet among urban graduates aged 22 to 32, joblessness remains in double digits. This contradiction is not statistical noise; it is structural.

By conventional measures, the economy appears healthy. Growth ranks among the fastest globally. Corporate profits have rebounded, equity markets are buoyant, manufacturing output is rising, and services continue to expand. Labour-force participation has improved. Yet employment outcomes lag. Regular salaried jobs, the backbone of middle-class stability, have grown too slowly to absorb a swelling working-age population.

Recent job creation has shifted towards insecure, informal arrangements lacking stability.

The Compression of Entry-level Work

For decades, output and employment moved together. Firms hired more people to produce more goods. That link is weakening. Across industries, productivity is being prioritised over labour intensity. Manufacturing shows this most clearly. Automation allows output to scale while headcount stagnates. Competitiveness improves. Employment does not.

Services are following a similar path. In information technology, labour-heavy models that once absorbed thousands of graduates are being replaced by AI-enabled systems. Routine coding, testing and customer support are increasingly automated. Revenues rise. Hiring flattens.

The damage is concentrated at the entry level. These roles were not merely jobs; they were training grounds where workers acquired skills, discipline and networks. As automation compresses the bottom rung, the ladder itself shortens. A labour market that bypasses beginners does not just reduce headcount. It restricts mobility. Growth becomes less inclusive because access narrows.

Capital Wins, Labour Waits

The deeper shift is towards capital-intensive growth. The capital required to generate one unit of manufacturing output in India has risen sharply, reflecting heavier investment in automation, plant and technology relative to labour. Output can now be scaled without a corresponding expansion in payrolls. Investment increasingly favours size, technology and balance-sheet strength over headcount, weakening the traditional link between growth and employment.

This shift weighs most heavily on small and medium enterprises, India’s main job creators. These firms face persistent constraints in access to credit, land availability, cash-flow predictability and contract enforcement. As compliance costs rise with scale, growing into formality becomes risky rather than rewarding. The outcome is a growth model that privileges ownership over employment. Profits rise. Labour demand lags. In an economy where informality remains widespread and reskilling systems thin, adjustment costs fall on households rather than institutions. Despite accounting for nearly 45 per cent of manufacturing output and over 60 per cent of non-farm employment, India’s MSMEs receive a disproportionately small share of formal credit and policy attention, leaving the employment engine underpowered.

A contrast is instructive. Germany’s Mittelstand is immune to automation pressures yet preserves the employment ladder. Mid-sized firms are supported by credit and vocational training systems that channel school-leavers into stable, skill-accumulating jobs. Productivity rises without hollowing out entry-level employment. India’s institutional design offers no such buffer.

Optimists advance two counter-arguments. Optimists argue India’s experience is global. Technology is decoupling output from employment. Others suggest missing jobs are invisible. Both claims contain truth. Neither resolves the central problem.

Growth That Carries

Platform work can expand opportunity for a minority with skills, capital and networks. For most workers, however, flexibility without security is not a substitute for mobility. In economies with strong safety nets and training systems, technological change is absorbed collectively. In India, where both remain thin, it is absorbed by households. The question is not whether new forms of work exist, but whether they can sustain a mass middle class in the way salaried, skill-accumulating jobs once did. So far, the evidence is unconvincing.

If India continues to produce output faster than livelihoods, job creation must move from the realm of social grievance to that of macroeconomic strategy. This requires re-centring policy on the “missing middle”: firms capable of scaling employment if institutional frictions are reduced.

Three shifts follow. First, a graduation buffer. A time-bound compliance holiday as enterprises cross size thresholds would shift the state’s role from enforcer to facilitator during the most fragile phase of expansion. Second, cash-flow reform. Allowing GST to be paid on receipt and expanding receivables discounting would unlock working capital for stable hiring. Third, portable social security. Benefits tied to workers rather than employers would lower the formality tax on hiring without weakening protection.

India’s tiger is running fast; it would be a pity if it ran alone

India’s next phase may be its fastest yet. But growth that fails to generate broad-based livelihoods carries political risks that numbers alone cannot absorb. A workforce that feels surplus to progress eventually turns sceptical of the system producing it; if India’s tiger runs too fast for its people to keep up with, it will eventually find itself running alone.

In the next phase, success will not be judged by how fast the economy grows, but by how long an elite-designed growth model can endure without the participation of those expected to sustain it.

Source – https://www.businessworld.in/article/the-job-problem-we-refuse-to-name-592126