In the past two years, Tata Consultancy Services (TCS), India’s largest IT services firm, has quietly let go of over 12,000 employees. This is not an isolated case. From 2023 to 2025, India’s top five IT companies—TCS, Infosys, Wipro, HCLTech, and Tech Mahindra—have cumulatively shed nearly 70,000 jobs, marking a sharp reversal from the hiring frenzy of the Covid-era.

Despite the relentless PR narrative around AI, digital transformation, and consulting pivot strategies, the truth is now evident: the job engine that powered India’s middle class is sputtering. This slowdown has an impact on the city economy across the country, and it will also reverberate in the small towns across India. While the leadership of these companies may have failed to plan for this eventuality, the policymakers have also not fully understood the impact of this job engine on future job growth.

A close look at the numbers tells a sobering story. Between FY21 and FY22, during the height of the pandemic, IT companies added employees at a record pace. TCS went from 509,000 to nearly 592,000, adding over 100,000 in a single year. Infosys grew aggressively, peaking at 345,000. Wipro, HCLTech, and Tech Mahindra all followed suit, hiring tens of thousands in anticipation of sustained digitisation demand from global clients. Attrition at this time hit unprecedented highs—Infosys saw nearly 28 per cent attrition in FY22—but firms kept onboarding to stay ahead of demand.

That hiring momentum came to an abrupt halt by FY23. By FY24, TCS had dropped to 601,000 employees, Infosys to 317,000, and Wipro to 234,000. Tech Mahindra lost nearly 7,000 employees, while only HCLTech held steady with marginal gains. FY24 was the first time in almost two decades that TCS reported a net reduction in its headcount. In total, across just two years, the top five firms lost close to 70,000 jobs. Every job in the IT sector creates 8-12 jobs downstream in the economy. These downstream jobs include the support ecosystem of maids, cleaners, consumption-based jobs in restaurants, and food producers, etc. The downstream jobs are generally blue-collar jobs. In the past, these companies would have moved these people to the bench, where they would be retrained or kept till such time as there were new projects. But the fact that these people have been asked to leave means that they cannot be retrained for new projects.

These are not cyclical cuts. They reveal a more profound structural change in the sector. The Indian IT industry was a manpower-based billing model—charging clients based on hours worked, not value delivered. India’s top IT services companies—TCS, Infosys, HCLTech, Wipro, and Tech Mahindra—have undergone a fundamental transformation in how they grow. For much of the last two decades, revenue expansion in Indian IT was almost always accompanied by aggressive hiring. But that link is now broken.

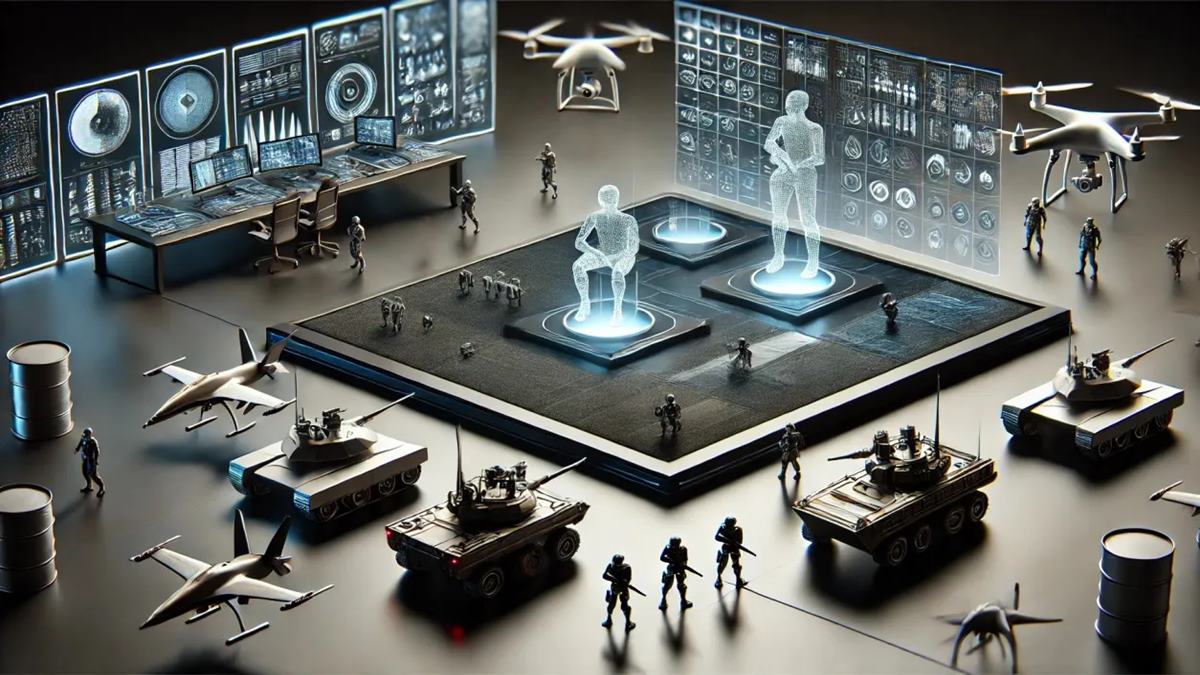

In the last two years, these companies have seen revenues grow, profits improve, and margins stabilise or even rise—all while headcount has either remained flat or gone down. This shift signals not just a cyclical slowdown in hiring but a structural pivot in how the industry scales operations now and in the future, increasingly relying on AI, automation, and specialised roles. This changes the hiring practices of the past, freshers and middle layers are most at risk, now.

TCS grew its revenues by around 3.8 per cent in FY24 to $29.9 billion, while net profit rose by nearly 8 per cent. But this growth came despite a headcount drop of over 13,000 employees in FY24—its first annual decline in almost two decades. Infosys, similarly, recorded a 7.5per cent year-on-year growth in revenue in the latest quarter and saw its net profit rise by over 8 per cent, even as it shed nearly 7,500 employees over the last year. HCLTech and Wipro saw similar patterns—mild to negative revenue growth, a reduction in employee strength, but gains in operating margins and profitability.

Wipro offers a particularly telling case. Despite its revenues declining for a second consecutive year, its profits jumped nearly 19 per cent in FY25, driven by cost control as its headcount shrank by over 5,000 in the last fiscal year. Yet it achieved greater revenue per employee and healthier bottom-line metrics. Tech Mahindra, too, has been on a cautious headcount trajectory, trimming employees even as it reorients toward higher-margin segments like AI, 5G, and digital transformation.

A consistent pattern across all these firms is the rise in revenue per employee, a critical marker of productivity. For TCS, it reached nearly $50,000; for Infosys, over $60,000; and for HCLTech, a similar level. These numbers reflect a shift away from labour-intensive, billing-hour models to outcome-based engagements powered by AI-based digital platforms. Tools like GitHub Copilot, AI Ops, and custom LLM integrations are enabling developers and engineers to deliver more code or value per unit of time, reducing dependency on sheer manpower.

This decoupling of revenue from hiring reflects a new stage in the Indian IT industry. The earlier era, built on linear growth—more projects meant more people—is giving way to a non-linear growth model driven by AI-based platforms, and AI-powered productivity. Automation is now being seen not just as a cost optimiser, but as a growth enabler. Instead of expanding campuses to onboard thousands of freshers, companies are focusing on hiring only domain specialists and investing in generative AI-led productivity tools that amplify the output of smaller teams.

This transition has implications far beyond quarterly numbers—it challenges the traditional model of IT employment as a middle-class engine of job creation. The HR departments that hired aggressively during the Covid boom are now implementing stealth layoffs, forcing “voluntary” exits, and reducing new hires. Workforce planning has collapsed, and the industry is quietly retreating from campus hiring. For lakhs of engineering graduates, especially from Tier 2 and Tier 3 towns, the pipeline to a middle-class life—however modest—has been severed.

This collapse is not just about freshers. The more dangerous tremor is hitting the middle layers of these organisations—the so-called email warriors. These are program managers, delivery leads, support staff, and PMO operatives—roles that primarily involve coordination, documentation, and oversight. With the advent of AI tools that can summarise meetings, auto-generate documentation, write code, and predict bottlenecks, these middle functions are rapidly being automated. These roles may not command headlines like coder layoffs, but their disappearance has far greater impact on urban economies.

In cities like Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Chennai, and Gurgaon, this segment forms the backbone of the local economy. They buy flats, pay EMIs, send their kids to expensive schools, frequent malls, and invest in SIPs. Their income flows sustain real estate, services, and urban consumption. A significant decline in their numbers — either through layoffs or salary freezes—will create a cascading impact on local economies. Already, reports from Bengaluru’s real estate sector show growing inventory in mid-tier housing and rising defaults in rental agreements by IT tenants. The ripple effect is real.

Now, many are pinning hopes on the GCCs to absorb the displaced workforce. But that’s a dangerous illusion. GCCs are leaner, more automated, and far less sensitive to domestic job sentiments. They will adopt AI faster and fire without warning—because they don’t depend on India for market perception, only cost arbitrage. If IT firms were the soft landings of the past, GCCs are likely to be the first to implement hard pivots.

What makes this more worrying is the government’s lack of recognition of the problem. White-collar job losses don’t show up in unemployment data. EPFO additions still show positives because of lag and contractual workers. There is no granular metric to track job loss in mid-tier urban tech roles. Policymakers continue to peddle a fantasy of AI creating lakhs of jobs. The recent narrative around “prompt engineering” as a career is one such example. While prompt engineers exist, the role is neither scalable nor foundational. It is transitional, a bridge skill—certainly not a substitute for the coding workforce of a million engineers.

The bigger challenge lies in our education pipeline. Engineering colleges across India, especially the private institutions that mushroomed in the last 20 years, were built to supply coders and testers to the IT services sector. That conveyor belt is now broken. If engineering education is to survive, it must reinvent itself—not around IT services, but around entrepreneurship, product building, climate tech, robotics, and domain-driven innovation. A civil engineer should not be taking a Java course to get a job. He should be designing infrastructure solutions using digital tools. AI should not be taught as a buzzword, but as a system-level capability integrated into domain learning.

For years, many of us have been warning of this implosion. I wrote to the industry body, cautioning them about the unsustainable growth in manpower-based models and the looming threat of AI. But the ecosystem is not wired for introspection. It rewards volume, celebrates headcount, and silences every voice that tried to speak about fundamental reform.